The following post is an edited and abbreviated version of the quarterly investment commentary that we recently sent to RPG clients.

A Jewish boy from Chicago is to blame. Harry Markowitz – a name that anyone who has ever taken a finance course might recognize – grew up in Chicago during the Great Depression. He went to the University of Chicago and in 1952, as a young 25-year old, wrote a paper titled “Portfolio Selection” that was published in the Journal of Finance. 38 years later, the concepts Markowitz explained in this paper and the supporting mathematical validations, contributed to him receiving the Nobel Prize in Economics. These concepts have served as the foundation of modern portfolio theory for more than 50 years.

Why blame Harry Markowitz? And blame him for what? The fundamental concept of Dr. Markowitz’s work is the dramatically simple concept that diversification reduces risk without sacrificing returns. Combining assets which behave differently into a portfolio – the essence of diversification – is, according to Markowitz, “the only free lunch in finance.”

But, this concept will always expose an investor to regret.

Imagine that you own just two investments: Super Stock Fund and Excellent Equity Fund. Aside from the rare occasion where the performance is identical, one will do better than the other. One will do worse. Even if Super Stock Fund gained 17% over the past year, you have reason to regret not owning more of Excellent Equity Fund which was up 24% over the same time period. And don’t forget about Next Door Neighbor Fund that you don’t own which gained 40%. Wish you owned some of that.

This is the way diversification works. There is always going to be something you regret owning. Often, multiple things. At this moment, you might regret not owning more of the S&P 500 Index and less of everything else. These US-domiciled stocks gained 10.4% over the prior 12 months. It is just that other assets failed to maintain pace with the S&P 500.

Blame Harry Markowitz, if you want. Blame Harry for diversification. Blame him for the fact that you will always have a reason to be disappointed. Because even if your portfolio was completely invested in the S&P 500 Index such that you earned 10.4% in the first six months of the year, you could be disappointed that you did not merely isolate to the utility sector which gained 19% over the same time period. Or that you did not have all your assets invested in Paysign, a payment processing company that gained 384% in the prior twelve months. Blame Harry.

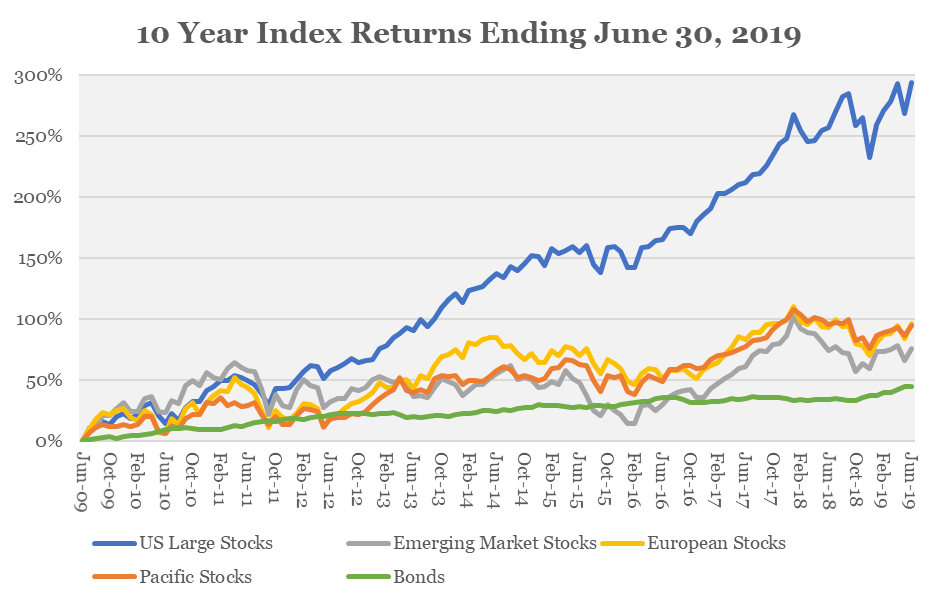

Diversification is hard and it can be hard for a long period of time. Maintaining a discipline to diversification is hard because there will always be something to regret. Consider how diversifying outside US large cap stocks has done this year. Or the last 10 years. Emerging market stocks have lagged the S&P 500 Index by 8.9% annually over the past decade. Stocks in developed Europe have lagged by 10.8% per year. Any diversification over the past decade has been a drag on performance.

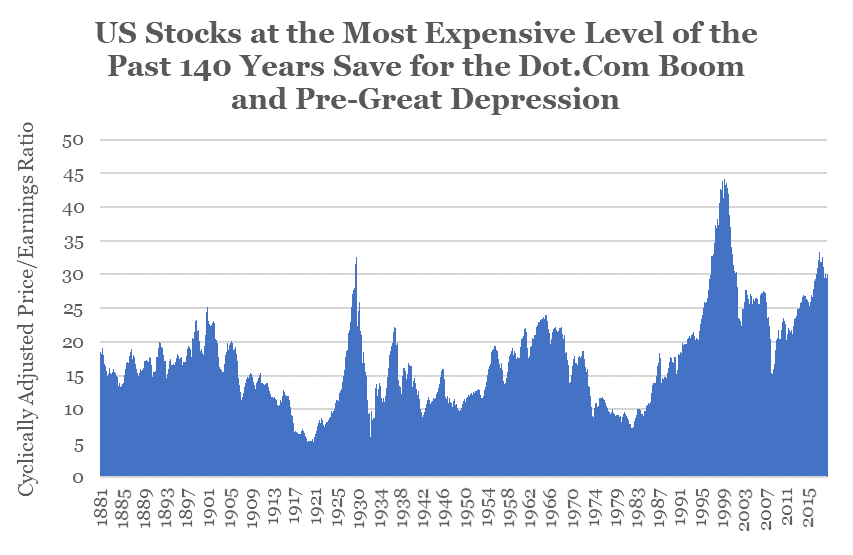

The last time, and the only other time in modern history, that US stocks outpaced foreign stocks by such a wide margin over a 10-year stretch was in the late 1990’s and early 2000. It was, as you may recall, the dot.com boom. US stocks did very well as valuations got lofty. Really lofty. Really expensive. In fact, the only occasions over the past 140 years in which US stocks were most expensive than they are today were the dot.com boom and two months in 1929 preceding the Great Depression.

Over the years that followed the dot.com market, foreign stocks more than tripled the return of US stocks (2001-2007). Emerging market stocks outpaced US stocks by a score of 350% to 26%. History will not repeat in the same way and it may not even look similar. But it is worth noting that not only have US stocks outpaced foreign stocks, they’ve become quite expensive in doing so. Stocks in developed Europe trade at a 38% discount to US stocks (as measured by cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio). The sale in other parts of the world is even greater. If there’s anything that matters to predicting future long-term performance, it’s current valuations and nothing else comes remotely close. Here is some evidence of that.

At a juncture like this, you could abandon all the evidence and empirical data to make the case that this time is different. You could load up your portfolio on the expensive large cap US growth stocks that have been the darlings of the investment world for the past decade. You could abandon diversifying investments, foreign stocks, and ignore valuations.

But any investment discipline ought to be underpinned by evidence and long-term data. Not evidence over the past decade. Evidence over the past century. And longer. Evidence implies that there will be extended periods that last as long as a decade where growth beats value or US stocks outpace foreign stocks by a wide margin. Evidence also indicates the long-term value of diversification and favoring cheap assets over expensive assets. Robust, persistent, pervasive, and economically intuitive evidence makes it clear that diversifying into foreign stocks, bonds, and different risk premia like cheap, value investments is the free lunch of finance. It’s a big free lunch that you don’t get every day. You get it over time.

Watching US large cap stocks continue to outperform every other asset class can be frustrating as a diversified investor. But, it is not a disaster and it is also not discrediting of diversification. Paraphrasing from investor Cliff Asness, the difficult part of sticking with diversifying strategies through tough periods is why they work in the first place. If they worked all the time or even nearly all the time, they would almost assuredly be scams.

Diversification means accepting the reality that there will always investments in your portfolio that you wish you didn’t own each day, each month, or each year. It means accepting that there will always be at least one investment that you wish you sold a year ago. And if you need someone to blame, blame Harry.

Have comments, questions, or additional thoughts? Please leave them in the comments section below.

Note that any specific references to returns or valuation metrics for emerging market stocks uses the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Similarly, references to US large company stocks uses the S&P 500 Index; European Stocks references the MSCI Europe Index, Pacific Stocks references the MSCI Pacific Index, foreign stocks references the MSCI EAFE Index, and bonds references the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index.

Very well laid out and articulated.