A number of years ago, we authored this article explaining why higher income parents may be well served to gift appreciated investments to their children and then have the children use the proceeds to pay for college. The article further explained how taxpayers who faced alternative minimum tax (AMT) received no tax benefit from claiming their children as dependents and how this reality made the strategy more effective.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that passed in late 2017 actually expanded the number of taxpayers who could benefit from such a gifting strategy and, in many cases, increased the benefit. Notably, a few important things impacting this strategy changed under the new tax law:

- Dependent deductions and dependent exemptions cease to exist.

- The “Kiddie Tax” was updated and now makes the gifting of appreciated securities even more favorable for higher income families (while less favorable for low income families).

- A new non-child dependent tax credit of $500 was established with an income phase-out for high-income taxpayers.

As a result of these important changes, we are updating the 2014 advice to reflect the new tax law. We again start by asking and answering some common questions, such as whether parents can or should claim a college-bound child as a dependent.

Can I claim my college-aged child as a dependent?

Yes, but there may be limited or zero benefit. While taxpayers will no longer receive any direct deductions or exemptions for child dependents, there is still one important tax break tied to dependent children for qualifying families – the child and dependent care tax credit which is worth as much as $2,000 per child. This credit requires that a child be under age 17 at the end of the calendar year and live with the parent(s) for at least half the year. As a result of the age limitation, college-aged children (with the rare exception of 16-year old college students like Doogie Howser) will not qualify.

All the tax news is not bad for parents with children in college. As noted above, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act created a new $500 “non-child” credit for any dependents age 17 or older. This tax credit has no age limitations and, in the case of a child, requires that the parents provides more than 50% of the financial support during the calendar year for him or her.

Importantly, both the child tax credit and the non-child credit begin to phase-out for married-filing-jointly taxpayers with more than $400,000 of adjusted gross income (phases out completely at $440,000) and single taxpayers with more than $200,000 of adjusted gross income (phases out completely at $240,000). For parents exceeding these income levels, there will be no tax benefit for any children or other dependents.

Should I claim my college-aged child as a dependent?

The answer is going to depend largely on parental income, since all the potential tax-benefits of a college-aged child depend on the adjusted gross income (AGI) of the parents.

Married Parents with >$440,000 AGI / Single Parents with >$240,000 AGI. Unfortunately, there are no tax benefits to claiming a dependent. As a result, parents above these income levels may benefit from letting their college student claim himself or herself as a dependent. This strategy will be explained.

Married Parents with $400,000 – $440,000 AGI / Single Parents with $200,000 – $240,000 AGI. The $500 per dependent tax credit is reduced by $100 for every $4,000 of income over $400,000 (married) or $200,000 (single). Again, parents with income in this range will receive limited benefit to claiming a college student dependent and may opt to let a child claim himself or herself as a dependent.

Married Parents with $180,000 – $400,000 AGI / Single Parents with $90,000 – $200,000 AGI. Parents receive the full $500 tax credit per dependent child. Again, there may be reason for parents with income in this range to forego the $500 tax credit in lieu of larger tax savings by not treating a child as a dependent.

Married Parents with <$180,000 AGI / Single Parents with <$90,000 AGI. In addition to the $500 dependent tax credit, parents with income below these levels may also qualify for the American Opportunity Tax Credit (maximum credit of $2,500 that is phased out entirely for married parents at $180,000 AGI) and the Lifetime Learning Credit (maximum credit of $2,000 that begins to phase out in 2018 for married parents with more than $114,000 of AGI). In order for a parent to claim either the American Opportunity Tax Credit or the Lifetime Learning Credit, the child must be claimed as a dependent on the parent’s return and so often it makes sense for parents with income below these thresholds to treat a college student as a dependent.

What about health insurance for my college-aged child?

Prior to 2014, not claiming a child as a dependent could make the child ineligible to remain on the parent’s health insurance plan. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) ended this concern. Per the ACA, children under age 26 can remain on a parent’s plan regardless of whether they are attending school, financial dependents of their parents, or married. That is, a non-dependent child can remain on mom or dad’s health insurance policy until age 26, regardless of whether the child is claimed as a dependent. The decision to treat or not treat a child as a dependent should not be influenced by health insurance.

What are the potential benefits of not claiming a college-aged child as a dependent?

The answer to this question depends entirely on the child’s ability to claim himself or herself as a dependent on his/her tax return. With a few exceptions, IRS rules state that a full-time student under age 24 can only claim the dependency exemption on his own if the student is providing more than 50% of financial support (food, shelter, clothing, education, medical, etc.).

Many parents tend to ignore the opportunity here, assuming that without a high-paying college job, son or daughter will not be able to meet the financial support test. However, parents would be wise to think outside the proverbial box and consider the significant potential benefits of gifting appreciated assets to a son or daughter.

Example 1: Two parents, Mike and Carol, have a daughter, Marcia, headed to college next year. The combined adjusted gross income of Mike and Carol is $500,000 so they will not qualify for the $500 dependent tax-credit or any other tax benefits of treating Marcia as a dependent.

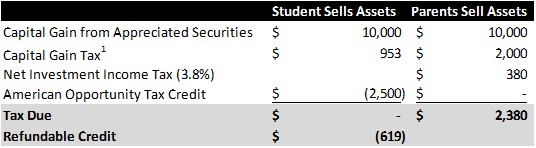

Marcia’s annual college costs (tuition, living expenses, etc.) are expected to be $50,000. In advance of these expenses, Mike and Carol decide to gift Marcia $30,000 of appreciated investments from their brokerage account where they own several highly appreciated investments. Marcia then sells the investments, recognizing a $10,000 capital gain.

Marcia uses the $30,000 investment sale proceeds to cover 60% of her expenses for the first year of college while Mike and Carol cover the remaining $20,000 (40%). Since Marcia covers more than 50% of her financial support with the $30,000 of investments that she owned and sold, she can file her own taxes and treat herself as a dependent. There are two big advantages – 1) Marcia will pay a lower tax rate on the capital gains; and 2) Marcia is now eligible for the $2,500 American Opportunity Tax Credit whereas Mike and Carol made far too much income to qualify for this credit on their return.

As a result of all of this, $2,380 of taxes are avoided – the amount that would have been owed had Mike and Carol sold the investments to pay for Marcia’s college expenses. Adding icing to the cake, Marcia also gets $619 back from the IRS since the American Opportunity Tax Credit is a partially refundable credit (40% of the calculated tax refund, up to $1,000 max: 40% of $1,548). Here is how it looks:

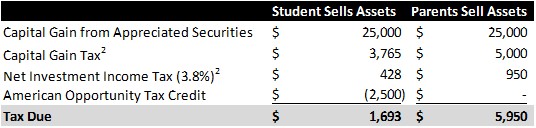

Example 2: Assume all the same information from the first example except that the appreciated investments have a gain of $25,000 rather than $15,000. The economics still work out very favorably but the calculation changes. Specifically, Marcia now faces a higher capital gains tax under the newly reformed “Kiddie Tax.” The last $11,250 of her gain is taxed at the same 23.8% capital gain tax rate that her parents would have faced.

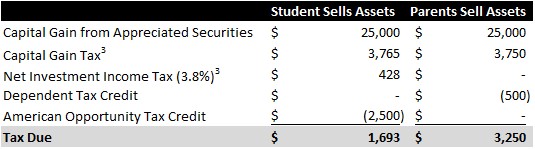

Example 3: Assume all the same information from the second example but now assume Mike and Carol have adjusted gross income of $200,000 rather than $500,000. Nothing changes if Marcia sells the investments. However, if Mike and Carol sell the investments, they face a lower capital gains tax rate (15% instead of 20%), they avoid the 3.8% net investment income tax, and they qualify for the $500 dependent tax credit – all because of their lower income. Even with these improvements, the math still works favorably for Marcia to sell the investments. Marcia qualifies for the American Opportunity Tax Credit while her parents do not.

Are there other benefits of this investment gifting strategy to allow a college-aged child to provide at least 50% of his/her financial support?

Everything to this point has yet to address the largest potential benefit of this investment gifting strategy – the improved ability for a child to qualify for in-state residency. Considering that most state universities charge $20,000 – $35,000 more per year for non-resident students to attend, the economic advantage of qualifying for in-state residency crushes the added tax benefits. In-state residency rules differ by state but almost all states are consistent in defining any student under age 24 who depends on his/her parents for financial support as legal residents of the same state as the parents. A few examples may help explain.

Example 4: Two parents are residents of Indiana and their 20-year old son, Kyle, attends the University of Virginia. Kyle’s parents pay for more than 50% of his expenses which means that he is the dependent of his parents for financial support and is automatically considered a resident of Indiana for tuition purposes. As a result, Kyle faces out-of-state tuition at the University of Virginia of $47,273 in 2018.

Example 5: The same two parents gift $100,000 of investments to Kyle with the idea that he will sell the investments and use the proceeds to cover 60% of his living expenses. During his freshman year, Kyle has total expenses of $60,000 and he covers $36,000 from the sale of gifted investments while his parents chip in to cover the remaining $24,000 with assets from a College Savings 529 Plan. Kyle also takes steps before his freshman year begins to establish residency in Virginia.

Since Kyle provides more than 50% of his own financial support and takes the other steps to establish domicile in Virginia, he can qualify for Virginia residency and in-state tuition as a sophomore. Notably, Kyle has to be domiciled in Virginia for at least a year and take steps (changing his drivers license, car tag, permanent mailing address, etc.) to demonstrate that he intends to make Virginia his home, indefinitely. Should he successfully qualify for Virginia domicile, in-state tuition drops more than $30k per year to $16,853.

Does the investment gifting strategy still save taxes if my child is not in college?

The answer entirely depends on the income and tax situation of the parents but it almost always will be tax-beneficial for parents to employ such a strategy. Importantly, we’re no longer talking about the dependency rules because this is not part of the equation. We are simply talking about mom and dad transferring appreciated assets to a UTMA or UGMA account in the name of a minor child and then liquidating the assets in such an account (at once or over time) to pay for permitted expenses related to said child like team sport costs, private school tuition, plane tickets, or summer camp (importantly, these accounts cannot be used for support obligations like food, clothing, or shelter). Provided there are legitimate non-obligation expenses that the parents would otherwise pay, what matters then is whether the parents pay a higher or lower tax rate for capital gains than the rate applicable if the children sell.

The revamped Kiddie Tax imposes the highest capital gain tax rate of 23.8% on capital gains exceeding $12,700 in a calendar year. For parents with high income that already pushes them into this 23.8% capital gains rate (taxable income for a married couple exceeding $479,000), the gifting strategy is advantageous on the first $12,700 of gains realized by the child because these gains are taxed at a lower rate. Moreover, even for parents who face the 15% capital gains rate, the strategy can still be advantageous on modest gain amounts. Consider the examples below.

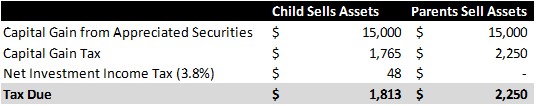

Example 6: The two parents of 10-year old Anna with taxable income in excess of $500,000 have an appreciated stock worth $20,000 with a gain of $15,000 that they wish to sell to pay for Anna’s private school tuition this year. Rather than sell the stock directly, they gift it Anna’s UTMA account and then sell the stock. In the UTMA account, the tax on the sale of stock is $1,813 – roughly half of what the tax would have been had it been sold by Anna’s parents.

Example 7: Everything stays the same as above except that the parents have taxable income of $200,000 and face a 15% capital gains rate on the stock sale.

As demonstrated in these examples, there is often a tax benefit to the gifting strategy even for children not in college. However, the important caveat to these examples is that Anna’s parents could not simply move appreciated assets to her UTMA account, sell the shares, and then use the funds for their own purposes. Once funds are in the UTMA account, the custodian of the account (presumably, Anna’s parents) may only use the money to serve Anna’s best interest.

What about gift tax and the limitations on gifting large amounts to children?

There are enough widespread misconceptions about the gift tax that we wrote this article to explain a few of them. Quoting from this article, “The idea of a $15,000 gift limit is, for most families, an antiquated and irrelevant concept that only gets in the way of rational decision-making about gift size. While there can be some ramifications for the castle-owning wealthy, this $15,000 figure (technically known as the applicable exclusion amount) really only comes into play for approximately 0.07% of the US population – those families with wealth in excess of $20 million.”

Closing Thoughts

The updated tax law continues to provide opportunities for parents to reduce taxes or even dramatically reduce college costs with smart planning. We address some of these opportunities above but the determination of what makes sense for each family could depend on other factors including the potential to qualify for financial aid, whether the child has earned income (all examples above are based entirely on “unearned income”), and the concurrent usage of College Savings 529 Plans. Additionally, we outline these strategies for a child but the same strategies could be used for a dependent or non-dependent adult family member. As usual, it’s important to consult with your tax advisor and financial planner before implementing such an approach.

Have thoughts, questions, or other suggestions? Have you utilized some of the strategies described above? Please do not hesitate to comment below with your suggestions or questions.

¹Marcia’s capital gain tax is calculated as follows under the new Kiddie Tax rules: first $1,050 at her rate of 0%; next $2,600 at the trust tax rate of 0%; next $6,350 at the trust tax rate of 15%.

²Marcia’s capital gain tax is calculated as: first $1,050 at her rate of 0%; next $2,600 at the trust tax rate of 0%; next $10,100 at the trust tax rate of 15%; last $11,250 at the trust tax rate of 20% plus a 3.8% net investment income tax on the last $11,250.

³Because Mike and Carol now have income of $200,000, they pay a capital gain tax of 15% on the investment sale and do not face the net investment income tax.