Paul Azinger is described by many as the best Ryder Cup captain ever. In 2008, he led what was arguably the least accomplished, least experienced, and least talented team of American golfers in the history of the Ryder Cup event – a 12-person team, missing the injured Tiger Woods and lacking a single player with a winning record in previous Ryder Cups. And yet Captain Azinger guided that 2008 US team to a decisive victory over the European team. Between 2000 and 2015, it was the only American victory in this biennial event.

In the lead-up to the recently concluded 2018 Ryder Cup, Paul Azinger was asked in an interview what single piece of advice he would give to the 2018 American captain. He responded, “Control the controllables.” The first step for the captain in this event, explained Azinger, was to come to grips with the reality that so many things, including where the golf ball went once the players teed off, would be completely out of his control. The second step was to focus exclusively on what he could control – the food at each meal, the pairings, the living environment, the setup of the golf course, and even the clothes that his players would wear. Control the controllables.

This fitting message for Ryder Cup captains is also one that near perfectly describes our investment approach. Ignore what we cannot predict or control, no matter how tempting. Focus exclusively on what we can control.

To be abundantly clear, we cannot control the direction of investment markets. No matter how hard we try or want. To further be abundantly clear, we cannot successfully forecast the direction of investment markets in the short-run or the precise timing of market sell-offs. No matter how hard we try or want.

Instead, what we seek to do is control the controllables. Where can we add controllable and evidence-based value? On the investment side, this comes from unexciting and not-so-glamorous activities like risk diversification, mechanical rebalancing, asset location, tax-loss harvesting, factor-tilting, and tax-aware distributions. Not. So. Glamorous.

It is often the case that even controlling what we can control results in unwanted outcomes. Adding uncorrelated strategies to a portfolio based on robust supporting evidence does not have unmitigated and uninterrupted success. To be frank, it often looks stupid. Billionaire investor Cliff Asness succinctly describes it well in a recent Bloomberg interview:

“There may be investment strategies that never, ever, ever have bad periods. A fair amount of those turn out to be scams; and even the real ones, the few people who have invented stuff like that, can’t run a ton of dollars, and they kick all the clients out. Real-world investment strategies that are relatively uncorrelated to markets and have positive long-term average returns and are scalable are hard to create. But they don’t generate win-every-day, win-every-month, win-every-year risk-adjusted returns.

We acknowledge and, speaking even for myself, suffer from many of the difficulties that come with sticking with such strategies through tough times. Of course, this difficulty is a big part of why we think the strategies work to begin with and are sustainable going forward. If sticking with them were easy, the threat of them being “arbitraged away” would indeed be much greater, and nobody would take the other side.”

In 2018, many of the most widely accepted and robust evidence-based investment strategies have suffered through a difficult period and presented headwinds to anyone who employs such an evidence-based investing approach. That is to say that controlling the controllables does not yield preordained success in all circumstances.

Headwind 1: Value Investing

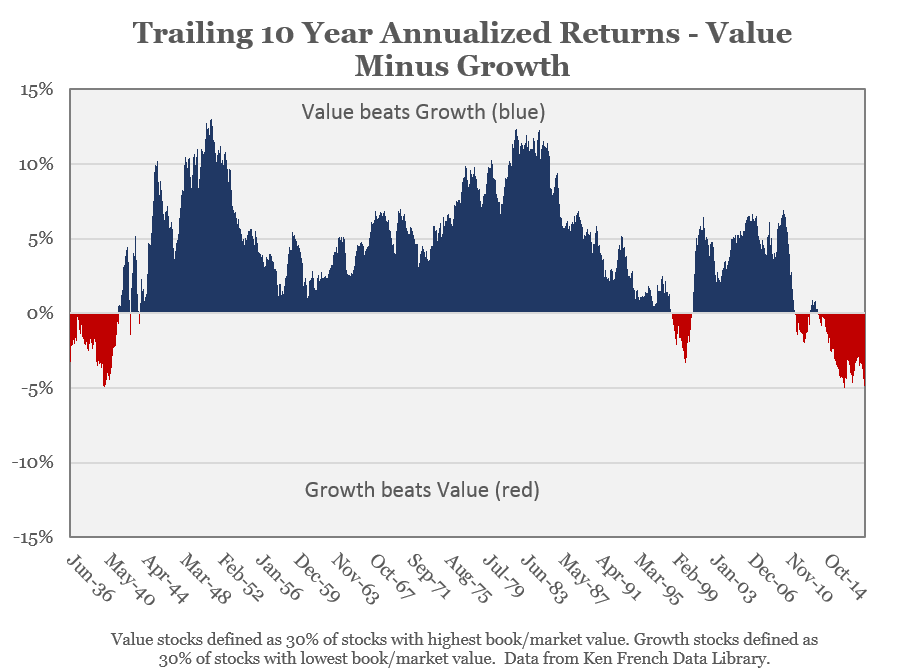

Most of our equity investments are tilted heavily toward value stocks. Why? Because value stocks (stocks with less expensive valuation metrics) tend to outpace growth stocks (stocks with more expensive valuation metrics) over extended time periods.  In every country. In every sector.

In every country. In every sector.

It’s called the “value premium.” We explained the intuition behind such persistent success in an article about value and growth investing:

Importantly, value stocks experience higher volatility of metrics like dividends and earnings which inherently make them riskier.

Higher risk means higher returns. Additionally, investors tend to consistently overestimate the persistence of growth for high growth companies and underestimate the ability of companies with depressed expectations to exceed those expectations. As a result, growth stocks often fail to live up to the implied expectations (which means they tend to be overpriced) and value stocks often tend to exceed the lowball expectations (which means they tend to be underpriced).

Value investing also owes some of its success to the lottery preference of human brains – an inherent behavioral desire we have to prefer long-shots at the racetrack or an exciting technology company with the small potential of a 20x return. Investors, as a result, pay more than they should for trendy growth stories or 100-1 race horses which, conversely, drives down their expected return. All these factors and others cause growth companies, in aggregate, to be overpriced relative to their intrinsic value and value companies to be underpriced.

A tilt towards value stocks has admittedly been a headwind in 2018. And it has not just been a headwind in 2018 – it has been a headwind for the last several years.

Yet neither the length nor the magnitude of this headwind is an unusual surprise.

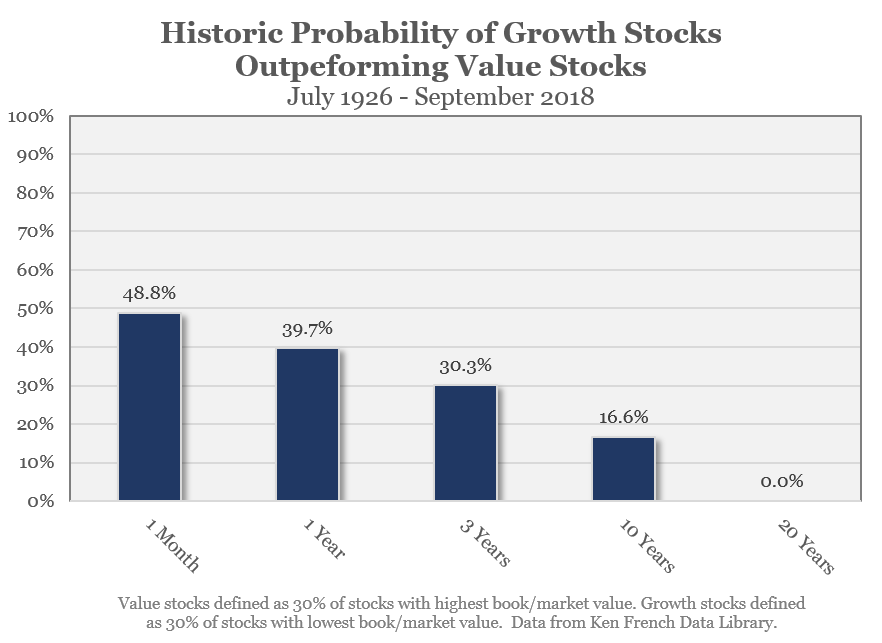

The reality is that such a headwind is to be expected for extended periods – and not just one quarter or one year or even three years. Imagine that you picked an arbitrary date between June 1926 and September 2015 to invest in a portfolio of value stocks for three years. Further imagine that your neighbor, over the same time period, invested in growth stocks. There is a 70% probability that you would have experienced success relative to your neighbor. But, that still means that there is a 30% likelihood, depending on the arbitrary date you chose, that you would be disappointed relative to your neighbor. That is to say that growth stocks have outperformed value stocks in 30.3% of historic 3-year periods.

Determining when value will again rule the day is difficult, if not impossible. There are plenty of possible catalysts for a market reversion back to favoring value stocks – rising interest rates, financial deregulation, higher oil prices, or a slowdown in consumer spending. However, we believe that trying to predict how long the growth-favored environment lasts is not a productive endeavor.

Headwind 2: International Diversification

Behaviorally speaking, diversification is miserable. The entire concept of long-term diversification squarely contradicts the ingrained temptations of homo sapiens. It is an admission that we, as investors, are not endowed with more and better information than the market. It lacks emotional thrills. You will not own enough of the high-flying glamour stock. You are unlikely to double your money in six months. There will be an emotional desire to always sell what is losing and buy what is gaining. It means you will always own investments that perform poorly relative to something else.

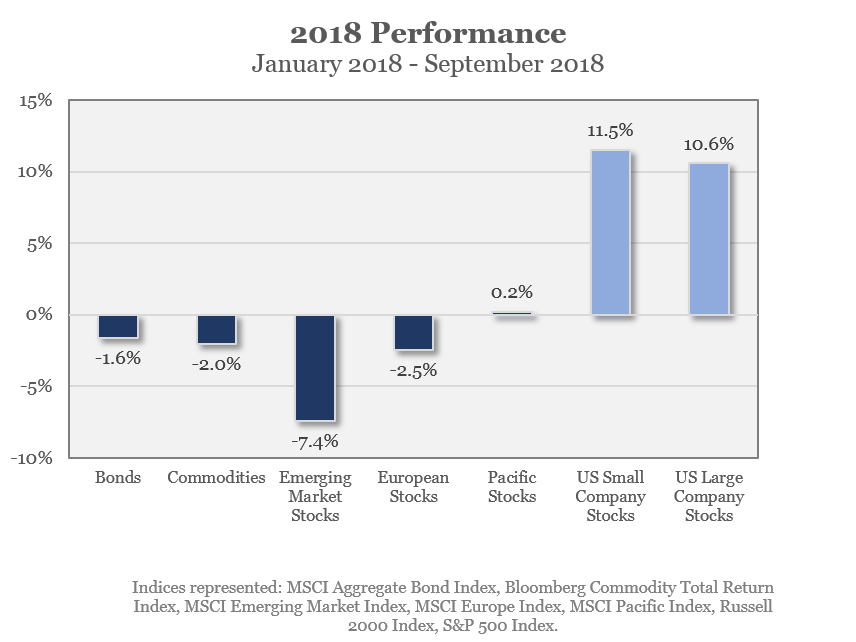

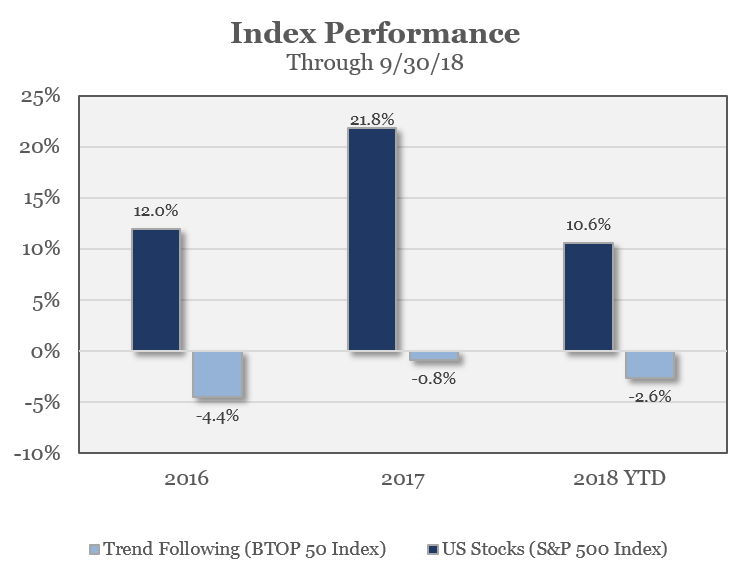

Of late, the something you wished you owned was US stocks. The something you wish you didn’t own was everything else. Every major asset class has trailed domestic stocks in 2018. And it hasn’t been close.  Owning foreign investments, bonds, commodities, real estate, hedge funds, or even Bitcoin meant the disappointment of not keeping pace with the market barometers quoted daily on TV, radio, and the Internet. In fairness, the S&P 500 represents approximately 25% of the world stock market and the Dow Jones less than 7%. Yet influenced by the inertia of mass media, most retail investors think of these benchmarks as the stock market.

Owning foreign investments, bonds, commodities, real estate, hedge funds, or even Bitcoin meant the disappointment of not keeping pace with the market barometers quoted daily on TV, radio, and the Internet. In fairness, the S&P 500 represents approximately 25% of the world stock market and the Dow Jones less than 7%. Yet influenced by the inertia of mass media, most retail investors think of these benchmarks as the stock market.

So why diversify? Why own stocks outside the United States?

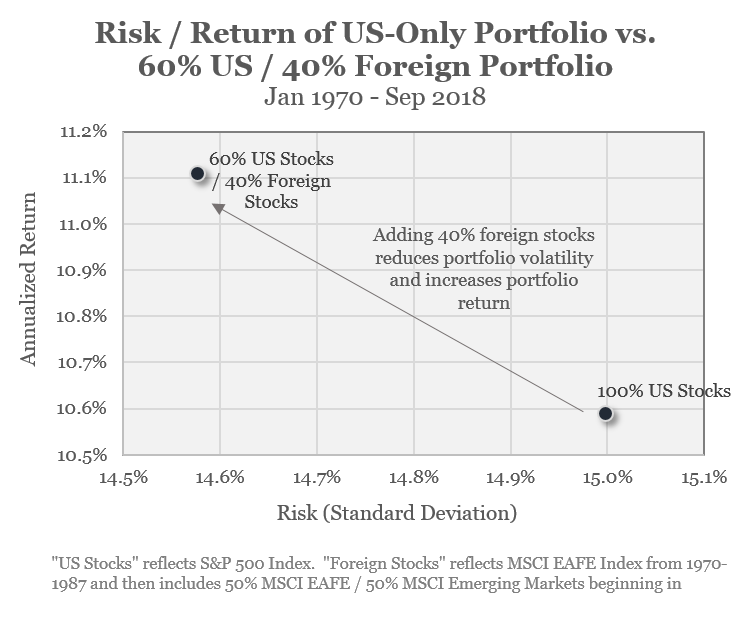

Because diversification provides the holy grail – higher returns and lower risk. Just not all the time. Foreign stock market data is available  going back to 1970. Constructing a portfolio over the subsequent 48-year period that includes both foreign stocks and domestic stocks beats a portfolio of only domestic stocks with higher returns, lower risk, and less severe drawdowns.

going back to 1970. Constructing a portfolio over the subsequent 48-year period that includes both foreign stocks and domestic stocks beats a portfolio of only domestic stocks with higher returns, lower risk, and less severe drawdowns.

Despite diversification’s long-term success, there are extended periods where the foreign diversification hurts. In fact, in nearly 50% of all years since 1970, a diversified investor would have regretted owning foreign stocks. But we contend that the same justification for consistently allocating to value stocks applies to consistently allocating to foreign stocks. Specifically, trying to determine the timing of when market leadership will change is an ill-fated proposition when juxtaposed against the compelling benefit of consistent foreign diversification.

Headwind 3: Trend Following

We utilize trend following strategies in portfolios for several important reasons:

- There is robust and pervasive evidence of historically strong risk-adjusted returns with low correlation to traditional asset classes for trend following strategies. As a result, adding them to a portfolio of traditional stocks and bonds tends to dampen portfolio volatility without sacrificing returns.

- There are economic and behavioral explanations of why trend following works and why such strategies should continue to work in the future.

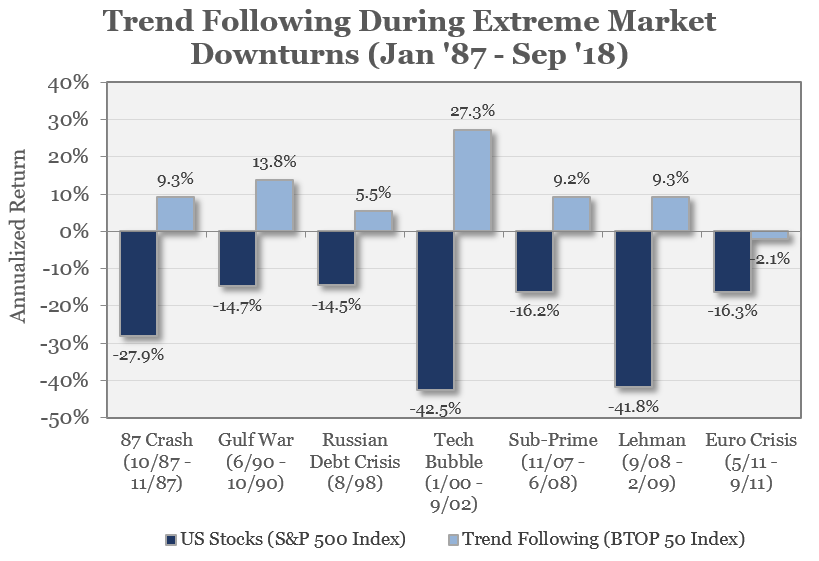

- These strategies historically provide valuable protection in difficult stock market environments.

These benefits of trend following strategies explain why we feel strongly about including them in a portfolio. However, the past several years made their inclusion in a portfolio feel like paying flood insurance premiums during an extended period of drought. That is to say that allocating part of the portfolio away from stocks and toward trend following investments has created a drag on returns just as paying insurance premiums creates a drag when there are no claims.

The adjacent chart shows the evidence of trend following’s crisis protection in every major stock market decline over the past 35 years. This, importantly, should not imply that these investments will always provide such protection. It does, however, paint a picture to help explain why we use this investment strategy in portfolios.

The adjacent chart shows the evidence of trend following’s crisis protection in every major stock market decline over the past 35 years. This, importantly, should not imply that these investments will always provide such protection. It does, however, paint a picture to help explain why we use this investment strategy in portfolios.

Closing Thoughts

We acknowledge that 2018 has been a tough year for diversification away from anything beyond US stocks. Economically intuitive strategies and diversifying investments that have provided the evidence of decades – and even centuries – of delivering strong returns to a portfolio have lately been a drag.

While this can be frustrating, it is not a disaster and it is also not, in our opinion, discrediting of diversification. Paraphrasing from Cliff Asness, the difficult part of sticking with diversifying strategies through tough periods is why they work in the first place. If they worked all the time or even nearly all the time, they would almost assuredly be scams.

Our plan is to continue using an evidence-based approached and to continue focusing on controlling the controllables. We believe that this continues to be the best long-term approach to consistently grow your wealth while producing the cash flows you need to accomplish your lifestyle goals.

As always, we invite you to contact us if you have any questions about global investment markets, your finances, or if you wish to review the health of your financial plan.

With warm regards,

Resource Planning Group

Leave A Comment