I got a flu shot in the fall of 1999. It is a seemingly trivial detail of life that should be long-forgotten but was, instead, memorialized by what followed. A few weeks after receiving this influenza vaccine, I suffered through the historic changing of the calendar from 1999 to 2000 with a debilitating flu. That 1999 flu shot was the first and only one in my adult life. In the winters that preceded 1999 and the 18 winters that followed, no flu vaccine and no flu.

My wife pleaded with me to get a flu shot nearly every year to follow and I stubbornly ignored the requests citing the infallible statistics. A more-than-two-decades-long perfect record of not getting the flu vaccine and subsequently avoiding the flu proved my case. Conversely, 100% of the times when I received a flu shot in my adult life, I ended up with the flu. The evidence was watertight.

Ultimately, my doctor rationally convinced me this past fall to ignore my personal evidence and get the flu shot. But it was not about ignoring the evidence. It was about embracing the evidence. The evidence is that flu vaccinations help adults reduce the risk of obtaining the flu by 40-60% in most years. The evidence is that flu vaccinations reduce the severity of illness such that for adults hospitalized with the flu, vaccinated patients were 59% less likely to be admitted to the ICU than patients who were not vaccinated.

The reliable and useful evidence comes not from the two dozen or so data points that I had personally collected but from the millions of data points collected by entities like the CDC. And the great irony of my decision-making framework to ignore the flu vaccination each winter was that it directly conflicted with the advice that I give nearly every day of my work life.

We talk as fiduciaries about “eating our own cooking” – about the importance of living the advice that we’re directly giving others. Yet here I was – for two decades – contradicting my own advice. Here I was relying on a small set of personal data and ignoring the much larger empirical evidence to irrationally make an important health decision. Like the other financial planners at RPG, I spend much of my work-life explaining the fallacy of small sample sizes and why the reliance on limited samples to make decisions often results in bad outcomes. The recognition convinced me to eventually look past my limited personal evidence on flu shots and rely on the more robust data.

So how are individuals making this same kind of mistake every day? The list of examples is enormous. Consider some of the common mistakes of extrapolating small sample sizes, with the qualification that there are plenty of examples beyond this sampling:

Relying on recent investment performance to make an asset allocation decision.

Example 1: Joe and Clara have returned 2% on their stock investments over the past three years. They learn that they can get 2.5% in a 12-month CD and choose to sell their stock investments to buy a CD where their “money is safe” and can earn a higher return.

Example 2: Cheryl looks at the performance of various indices and sees that the German stock market gained 38.8% over the past 12-months. As a result, she elects to allocate more of her investment portfolio to German stocks.

Example 3: Mildreth inherited a significant amount of gold but wants to wait on selling because the price of gold is up 45% over the past 36 months.

Relying on recent investment performance to choose investments.

Example 4: Henry compares the three-year performance of the fund choices in his 401k and allocates all his 401k dollars to the four funds with the best three-year returns.

Example 5: Bob relies on 5-year investment returns to select investments, picking only fund managers with 5-year performance above their respective benchmarks.

Relying on recent investment performance to make capital allocation decisions.

Example 6: Nancy’s three-year annualized investment return is 1.2% and her mortgage rate is 4.0% so she decides, based on this information, that she is better off using her recent bonus to pay off her mortgage than to invest the funds.

Example 7: Chris is planning to buy a new home and use cash from his portfolio to fund much of the purchase. He asks what his five-year investment return is. When told that his annualized return is 14.2% and that his available mortgage rate is 5.5%, Chris elects to borrow to buy his new home rather than using funds from investments.

Relying on recent performance to make purchase or sale decisions.

Example 8: Brent and Debbie need a significant amount of cash for a major home renovation but decides to hold off on the renovation because the market has been doing so well of late.

Example 9: Joan has a large cash inheritance but wants to wait to invest any of the cash because his brokerage statement value is down over the past 12 months.

None of these examples is far-fetched. Just the contrary. All of these are real examples with only names and facts adjusted to maintain anonymity. And to avoid mincing words, all of these examples showcase lousy ways to make decisions.

In every one of the anecdotal examples above, individuals use information to make decisions. The problem is that the information, because of the small sample size, offers no useful value. The decisions may end up being correct but it won’t be because of the way they were made. Just like hitting on 19 in blackjack and getting a 2 to make 21 may win money but it doesn’t justify the decision.

I justified not getting the flu vaccine as informed because of my personal experience. This decision was terribly misinformed given all the robust information and data I could have used. The truth is that we tend to consistently rely on small sample sizes to make decisions when the rational outcome would be to rely on robust empirical data to make far-more informed decisions.

As it relates to investing, the evidence makes it overwhelmingly clear that relying on small sample size is egregiously unhelpful. Regrettably, mutual fund marketing promotes things like 3, 5, and 10 year returns or Morningstar star-ratings, which are based largely on 3-5 year historic returns. Yet, pervasive evidence is abundantly clear that past performance is an atrocious determinant of future performance. Morningstar – a company that made its fame and riches on the star rankings of mutual funds – has, on several occasions, debunked its original star-rating methodology that relied on past performance. Research actually suggests that investors would be better off buying funds with poor recent performance and selling funds with good recent performance. Such evidence provides a telling indictment about the utility of past performance as an indicator of future performance.

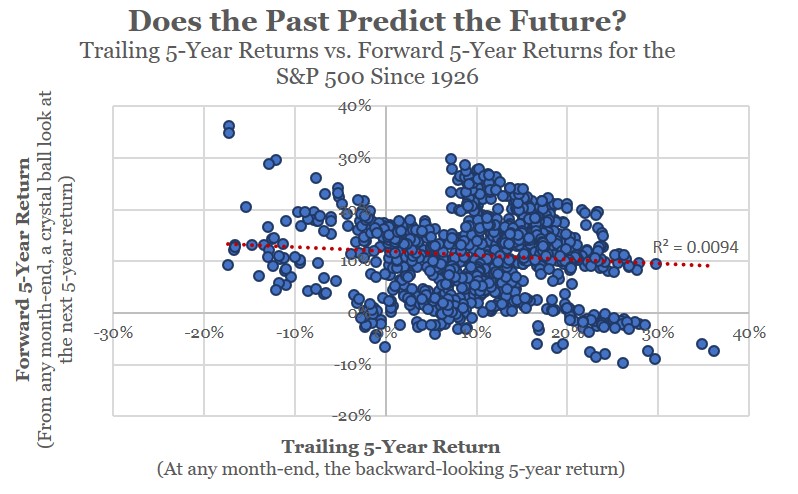

Many of the examples above rely on recent market returns to make decisions about the future. In reality, extrapolating the small sample size of recent market returns into the future is counterproductive. The following chart plots the look-back 5-year S&P 500 return for every month-end since 1926 (on the horizontal axis) relative to the forward-looking return for the next 5-years. If 5-year market returns were indicative of the future, we would see the data points forming a clear line from the bottom left corner to the top right corner.

Instead, the plots demonstrate that past market returns offer effectively zero explanation of the future (less than 1% of variation from the average market return is explained by past performance).

The lesson learned is that you might as well use a coin toss to predict the market’s return over the next five years rather than to rely on the past five years return to make a prediction about the next five years.

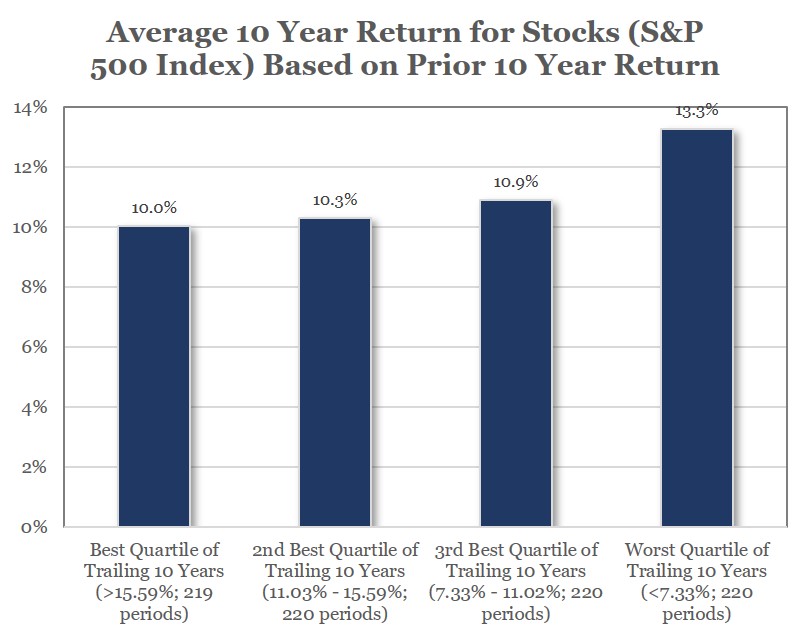

Furthermore, if there is any helpful relationship between past returns and future returns, it relies on a longer period and the relationship is actually negative. On average, the best 10-year returns for stocks have followed the worst 10-year returns for stocks. Conversely, the worst 10-year returns for stocks have come after the best 10-year returns for stocks. If Joe and Clara from Example 1 or Nancy from Example 6 are going to use their personal data to make decisions, their preferred action would have been to do the opposite of what their extrapolated short-term historic results suggested.

Closing Comments

What should we do differently? How about the next time you face a decision of whether to invest cash or raise cash, do not allow the last 3, 5, or 10 years performance history to impact the decision. The next time you’re deciding whether to pay off debt or not, don’t use personal performance or recent market returns as a decision factor. If you’re ever evaluating mutual fund choices, ignore historic returns to make buy/sell decisions.

And just get the flu shot. For what it is worth, we’re almost through flu season and the flawless record of getting the flu shot and catching the flu is in jeopardy.

Leave A Comment