It is difficult to go more than a week without seeing or hearing advertisements for an investment that guarantees zero risk of principal loss, promises an attractive return (5-10% per year), and insurers lifetime income that never expires. Admittedly, these promises can sound very attractive on the surface, especially for risk averse investors. But are they too good to be true? If so, why?

Such advertisements promote a number of different investment product structures – products such as guaranteed fixed indexed annuities, structured notes, and variable annuities with guaranteed minimum withdrawal benefits.

Our objective here is to explain the hidden drawbacks of one popular product type – the variable annuity with a guaranteed lifetime income option (GLIO). Notably, we will not explain every nuance of the product type as that will take far more words and pages. We will instead explain some of the important, but often hidden drawbacks of the GLIO annuity. In order to tackle do so, we use the terms of a real life guaranteed lifetime income annuity as an example. This widely advertised product is commonly marketed with a Lifetime Income Rider option that provides a 7% guaranteed return for the first 10 years.

Before we proceed, it is important to make clear that this type of investment is not specific to any one insurer. In fact, most insurance companies offer very similar versions of the same annuity product. The challenge for consumers is to understand the key drawbacks of this annuity structure. On the surface, a 7% guaranteed return sounds great, but it is up to the purchaser to read through a dense prospectus and supplements to recognize where the drawbacks may be. That said, we use the remainder of this post to dive into a few of the under-publicized drawbacks of this variable annuity type.

The difference between simple interest and compound interest is like the difference between a Weight-Watchers dinner and an all-you-can-eat buffet.

Here’s the thing – promotional materials often state that the guaranteed return from these products is a simple interest return. This means that on a $100 investment, you earn $7 in year one, and $7 in year 2, and so on. The issue is that many investors fail to appreciate how dramatic a difference there is between simple interest and compound interest over extended periods. Moreover, insurers are unlikely to highlight the significant disadvantage of simple interest.

$1,000,000 earning 7% simple interest becomes $1,700,000 after 10 years. Alternatively, $1,000,000 earning 7% compounded per year in the way we traditionally think of returns becomes $1,967,151 after 10 years. The seemingly subtle difference in terms results in a difference of $267k – not small potatoes. Over 15 years, the difference grows to $709k and the 7% simple return actually calculates to a 4.9% compound return.

This is not to imply that insurance companies mislead consumers by using simple interest. It is, instead, to say this subtle difference in terms is likely not fully appreciated by annuity customers.

You’re forced to pay $9.50 for a 12 ounce can of Bud Light.

Unlike a traditional brokerage account or IRA where you can choose from over ten thousand mutual funds, these annuities have a defined list of the funds to which you can allocate. In fairness, the issue with the annuities is not the lack of investment choices, it is the lack of low cost investment choices. According to our research, the lowest cost investment option out of more than 100 funds in an annuity we looked at is the S&P 500 Index Fund option that had an annual fee of 0.49%. While this stacks up well against most of the other investment options in the annuity that charge north of 1% per year, it looks egregious when compared to other S&P 500 Index funds that have a nearly identical portfolio. The Vanguard 500 Index, for example, charges 0.05% per year. This 0.44% difference in fees adds up to nearly $45,000 of additional cost for a million dollar investment over 10 years.

The reality is that these variable annuities offer expensive share classes of what might otherwise be good funds. Think of it as buying beer at a major league baseball game. Whereas you can buy a case of Bud Light in the grocery store for under $1 per 12 ounce can, the same beer may cost you $9.50 at the ballpark. The variable annuity basically treats you like you’re at a major league baseball game, minus the cracker jacks, peanuts, and baseball game.

The expensive beers are one thing, but you’re also paying a fortune to get into the game.

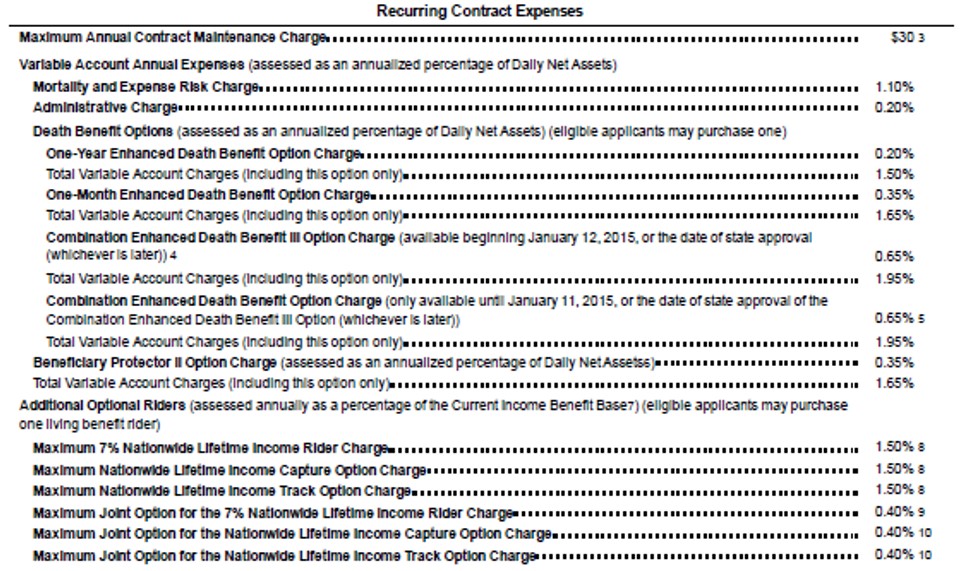

It would be one thing if only the investment fees were high but these are just one layer of fees in a multi-layer fee cake. To receive the 7% guarantee in the annuity we reviewed, one pays an M&E charge of 1.1%, an administration charge of 0.2% and a lifetime income rider charge of 1.2 – 1.5%. That all adds up to an annual fee of 2.5% – 2.8%. Any growth you hope to achieve in the contract value has to fight against this annual headwind plus the additional headwind of the high underlying investment fees described above. In an environment where bond yields are already low, it’s quite the challenge to overcome fees in excess of 3%.

Moreover, keep in mind that we’re being generous with the fees. While these total annual fee of 2.5% – 2.8% should rightfully sound expensive, this really only gets you upper deck bleacher seats at the game. Want other options like an enhanced death benefit or a joint life annuity? These other annuity options have additional expenses as depicted below.

The promised return might be useful if you could actually access your money.

The annuity we reviewed provides a 7% guaranteed return on something called the “income benefit base” and this is again where terminology becomes really important. Notably, the income benefit base and the contract value are two separate things.

The contract value is the total value of your investments inside the annuity. Just like in a traditional brokerage account, you make or lose money after fees and this is money that you can withdraw. In an annuity, this is the contract value. This value goes up or down each business day but the 7% guarantee is not applied to this contract value.

The income benefit base is an alternatively calculated figure to which the 7% guarantee is applied. However, the income benefit base is not yours to withdraw at will. To access this income benefit base, you must annuitize (i.e. elect to draw an annual pension from the contract) at a rate that is set by the annuity contract. In the case of the annuity contract we reviewed, the lifetime annuity withdrawal rate for someone between age 59.5 and 64 is 4.25% and the rate between age 65-74 is 5.25%.

Here is the key point – since the annuity provider sets the annuitization rate, the guaranteed return, in isolation, is meaningless. Forget a 7% guaranteed return – an insurer can sell an annuity with a 15% guaranteed annual return (again, simple return) for the first 10 years. If the insurer concurrently says that after 10 years, the buyer can annuitize this income benefit base at 2.5% per year (the annuitization rate), the contract doesn’t actually pay out its first dollar of gain until year 27. Up to that point, the annuity buyer is merely receiving a return of original principal. Looked at this way, the 15% guaranteed return may not sound as appealing.

Now consider the 7% guarantee. If you were to purchase this annuity at age 54, annuitize after 10 years of the guaranteed 7% return, and live to the age of 83 (expected longevity based on mortality tables), the rate of return (IRR) over the 30 years comes to 1.62%. It’s hard to get excited about an illiquid investment product that promises a 1.6% annual return over 30 years which is why the annuities are not marketed this way.

Conclusion

Admittedly, there is a lot more that we can explain about these types of guaranteed lifetime income annuities. We ignored the hefty surrender penalties during the early years of the contract but also the benefit of lifetime income provided by these products (which may be better achieved through different annuity products). The reality is that there can be a place for annuities with guaranteed income riders such as this although we would argue the pool of appropriate users is much smaller than the pool to which it is marketed and sold.