On a recent visit to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), I surprisingly stumbled upon an exhibit featuring classic video games such as Tetris, Asteroids, and Pac-Man. The games were displayed on active video screens with an adjacent explanation of the creativeness or design elegance for why they were each chosen.

In their heyday, these games were revolutionary relative to video game predecessors and launched the golden age of arcades and video gaming. Fast forward roughly thirty years and the graphics of these games are a grainy and rudimentary version of modern video game technology. Not to take anything away from these early games but video graphics have advanced so far in the past 30 years that millennials now mock these antiquated graphics.

A lot has obviously changed in the past 30 years and financial services is no exception. Yet many investors still hold on to legacy concepts that were popular in the 1980’s but should have been leapfrogged like Asteroids graphics. One common example is the practice of retail investors building a portfolio comprised of a few individual stocks. This practice of investing in individual stocks became popular in the 1970s and 1980s as households gained access to stock markets and dividend reinvestment programs (DRIP programs).

Looking back on this period, one can easily defend the practice of individual investors constructing a stock portfolio.

- Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) did not exist and the mutual fund industry was still in its infancy.

- International diversification was hard to achieve, so a US-only portfolio was practical.

- DRIP programs made stock investing cheap and easy, relative to other options.

- The investing competition was mostly other unsophisticated investors.

- Behavioral research had yet to demonstrate how poor individuals are at investing.

Developments over the last 30 years should have largely ended the inefficient exercise of retail investors buying and selling individual stocks. Yet the practice still continues in large number despite the reality that there are better alternatives.

Be Careful Competing Against Pro Athletes

As a 27-year old analyst at a large mutual fund company, I dedicated a month to the analysis and future projections of every single line item on PepsiCo’s financial statements. I spoke with suppliers, merchants, and executives and learned way too much about the economics of oatmeal or trends in the chip and dip market. My company literally spent millions of dollars to get unique information and research, giving me perspectives that were light years removed the information available to individual investors. I witnessed first-hand the extreme research and trading disadvantages faced by personal investors when buying or selling securities.

But that is not all. I further realized that there were plenty of competing businesses with even faster access, more information, better analytical tools, and countless computer scientists, Ph.D.s, and mathematicians each spending countless hours analyzing the same company. The esteemed Charles Ellis wrote in a 2014 Financial Analysts Journal article, “Over the past 50 years, increasing number of highly talented young investment professionals have entered the competition for a faster and more accurate discovery of pricing errors…They have more advanced trading than their predecessors, better analytical tools, and faster access to more information.”

In order to achieve excess profits by owning any single stock, an individual has to know something that the marketplace does not or have access to material, non-public information that provides an advantage. The latter is illegal. The former may be possible with enough time and work but individual investors generally fail to appreciate that they’re competing against well-funded Wall Street and hedge fund teams with infinitely better access, resources, and information.

Few well-reasoned individuals would consider lining up against NFL professionals in a game of full contact football. Yet this happens every day when individual investors line up against professional investors. 40-60 years ago, your neighbor, co-worker, or dentist was likely to be on the other side of the stock trade from you. Retail investors made up 90% of all stock trading following World War II and that percentage gradually declined to roughly 50% by 1980. Today, there is a greater than 90% chance you’re trading against a professional. Said differently, there is a better than 90% chance that you are suiting up against an NFL linebacker.

Individual investors have become the unknowing victim in a zero-sum competition where there has to be a loser for every winner. Despite the extreme disadvantage, they are persuaded by online brokers, traditional brokers, and Jim Kramers of the world – all who benefit financially when individual investors trade more – to keep competing against the professionals. They’re convinced to keep stepping up to that line of scrimmage to get sacked again by Ndamukong Suh.

Forget Pro Athletes, Be Careful Competing Against History

Some may still believe they have the skill, resources, and access to unique information to successfully select a few individual stocks. Some people admittedly do. So now consider the empirical evidence working against individual investors who compile a concentrated stock portfolio.

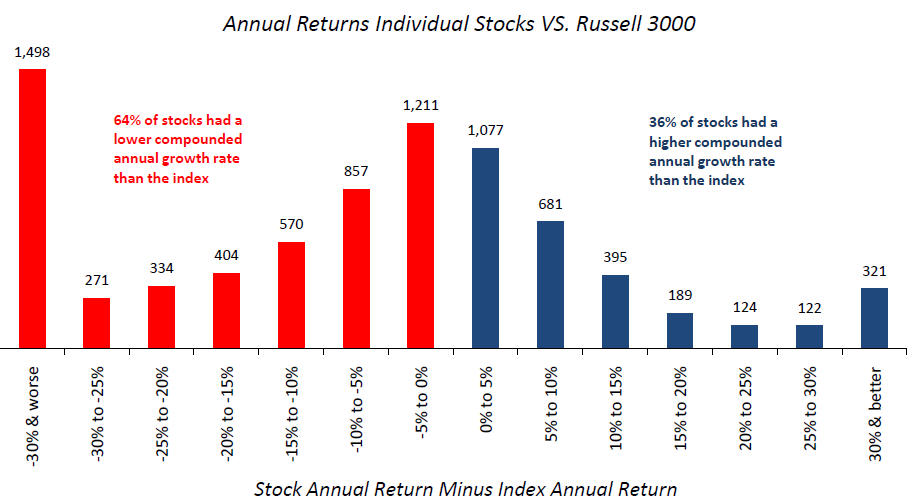

If stock returns were normally distributed, then half the stocks would perform above average and half would perform below. You or I could buy any stock and have a 50% chance of being above average. However, individual stock returns are not normally distributed. A handful of stocks produce large returns and account for all of the market’s gains while the vast majority of stocks underperform.

Between 1983 and 2007, if an individual purchased any stock, there was a 64% chance he or she underperformed the index. Furthermore, during arguably the greatest bull market ever, there was a 39% chance an investor would have lost money in any single stock. The Russell 3000 returned 1,784% over this 25-year stretch during which nearly 2 out of 5 stocks lost money. A chart below from “The Capitalism Distribution” study demonstrates this asymmetric distribution of stock returns.

The point is that not only are you competing against professionals when you buy individual stocks but you’re facing a stiff competition against the skewed non-normal distribution of stock returns.

When Offered a Free Lunch, Stack Your Plate High

Diversification is often called the only free lunch of finance. It gets this moniker because proper diversification allows investors to reduce the level of risk without sacrificing return or, alternatively, increase the expected return without higher risk. Most seasoned investors tend to think of the financial free lunch like a college student thinks of the real thing – pile the plate high and take as much of the free lunch as you can get.

The scholarly reason for this free lunch lies in the fact that failure to properly diversify is a choice, not a limitation. In very basic terms, there are two types of risk when you invest in stocks. The first is systematic risk which includes things like an economic slowdown, a major earthquake, or a terrorist event. These are unavoidable risks that you take whether you own one stock or thousands.

The second type of risk is called idiosyncratic risk or unsystematic risk. These are the risks incurred with stock of a single company. The company may be filing fraudulent tax returns or falsifying earnings that later get discovered. Perhaps the company’s CEO unexpectedly dies, the company’s technology becomes obsolete, or it is discovered that the company’s product causes cancer. These risks are not rewarded by increased expected return because they are easily avoidable with proper diversification.

If you play blackjack in Vegas with your eyes closed and win, you do not earn any more money than if you played with your eyes open. When it comes to investing, owning 1 stock instead of 100 does not provide a higher expected return – it simply provides greater risk. You do not get paid more for taking these idiosyncratic or avoidable risks which makes owning a few individual stocks synonymous with playing eyes-closed blackjack.

It’s More Expensive and Takes More Work to Buy Individual Stocks

It used to be cheaper to buy a basket of individual securities instead of an expensive mutual fund. With diversified index mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) now available for less than 0.1% per year, buying 25-30 individual securities now tends to be more costly when considering implicit and explicit transaction costs. Additionally, any individual who is adding money to or distributing funds from a portfolio of individual stocks each month faces the arduous and otherwise costly process of buying and selling multiple stocks each month.

Practical Implications

This is all not to say that buying individual securities is a futile cause. There are certainly investors with unusual access to information or unique skills who can be successful trading a portfolio of individual securities. The challenge is that the battle is uphill, the task is arduous, and the competition is intense.

The reality is that some people still enjoy playing old school versions of Tetris and Asteroids even though today’s games have infinitely better graphics, load far faster, and offer more options. There’s nothing inherently wrong here. They make this decision by choice, knowing that more modern options exist.

Whereas little to no marketing dollars are spent compelling individuals to play video games from 1981, huge amounts are spent by brokerage firms convincing the public that they should buy and sell individual securities as if it was still 1981. In the end, this may never change as there is plenty of money to be exploited by the promotion of this legacy practice and our society of overconfident human beings have the innate desire to speculate. The great Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Zweig cogently summarizes the unfortunate reality of financial services:

“In the short run, you can make a little money by lying to people who want to hear the truth, or a lot of money by lying to people who want to be lied to. But you can’t ever make any money by telling the truth to people who want to be lied to.”

Leave A Comment