Related Posts:

When ROTH is Wrong: Follow-Up Q & A

Opportunity for High Income Earners – the Backdoor Roth Conversion

More than 50,000 visitors in 2021… click here to sign up for our newsletter and never miss a post!

(Don’t worry, we will not take up too much space in your inbox. After four fun introductory e-mails, you can expect to hear from us every 6-8 weeks.)

On to ROTH savings and when it may not be the right choice….

In his book Predictably Irrational, author and esteemed behavioral psychologist Dan Ariely wrote an entire chapter about the strong emotional impact of getting something for free. He describes how we go back for free extra courses at the buffet despite not being hungry or how we wait in line for an hour to get a free scoop of ice cream that would have cost $4 any other day with no wait. Ariely highlights several studies that demonstrate how consumers are overwhelmingly more inclined to choose free items relative to something that costs $0.01. He also references data from online retailers which demonstrates how consumers overpay in total cost for items with free shipping or buy extra items that they don’t want or need just to qualify for free shipping. My personal favorite story cited by Dan Ariely is the one where a researcher polls 76 people standing in line to get a free tattoo and finds that 68% would not get a tattoo if they had to pay for it.

There’s something about free. We make irrational choices when faced with faced with free goods or services. The behavioral explanation is that humans are overwhelmingly afraid of loss. When something is free, humans inherently have the perception – often without validity – that there is no risk of loss.

But the price of free rarely ever is free. Consider the unwanted tattoo on your forearm, the lost hour spent to get “free” ice cream, or the extra book which will never be read that was added to your shopping cart to get “free” shipping.

In financial planning, this irrational fandom of free impacts how savers view Roth accounts. The tax law maintains that once money goes into a Roth IRA, Roth 401(k), or other Roth account, the future growth on those dollars are free. Money goes in, it grows, and then it comes out…tax-FREE.

It is likely the yearning for free that irrationally drives smart people to make poor financial choices as it pertains to Roth accounts. The objective for many disciplined savers is to fund their Roth accounts, let the investments grow free of tax, and then have tax-free money to spend in retirement. Free, free, free. Unfortunately, the downside of this plan for most high-income earners is that it will cost them far more in current taxes than they will save on future taxes. Ultimately, the tax-free attraction of Roth accounts tends to be a lousy decision for most high-income savers, resulting in far less post-tax wealth or spending power. And yet smart people still contribute to tax-free Roth accounts, perhaps not appreciating the significantly negative financial impact that it is likely to have.

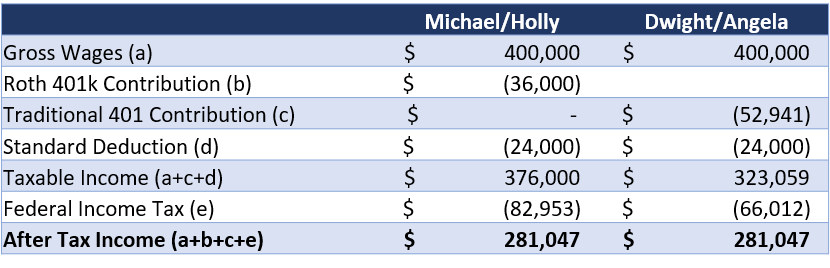

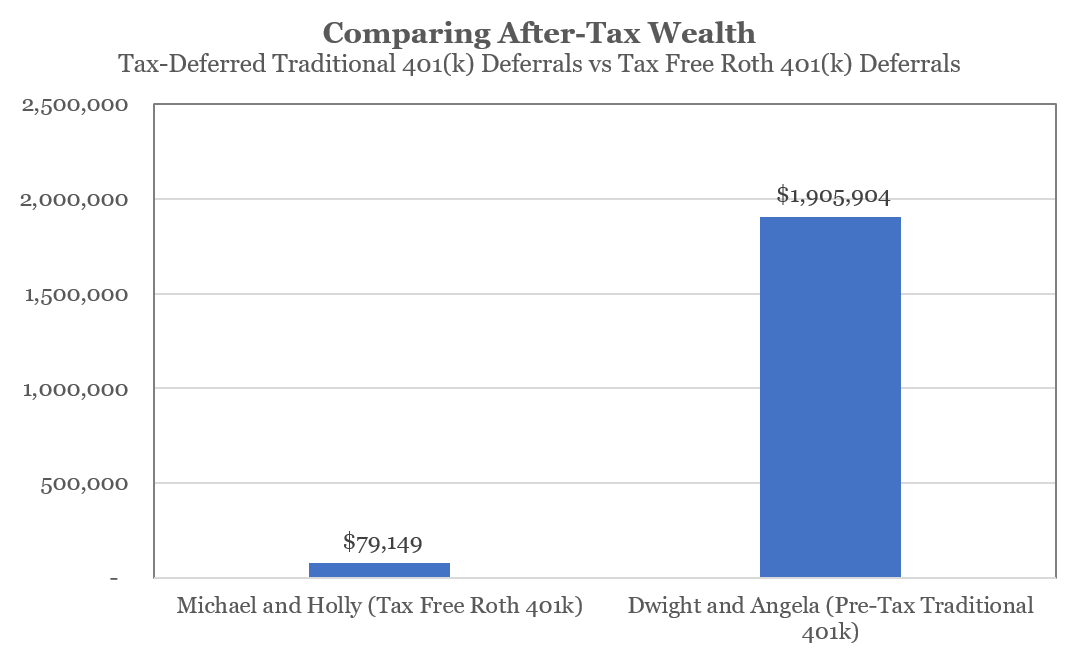

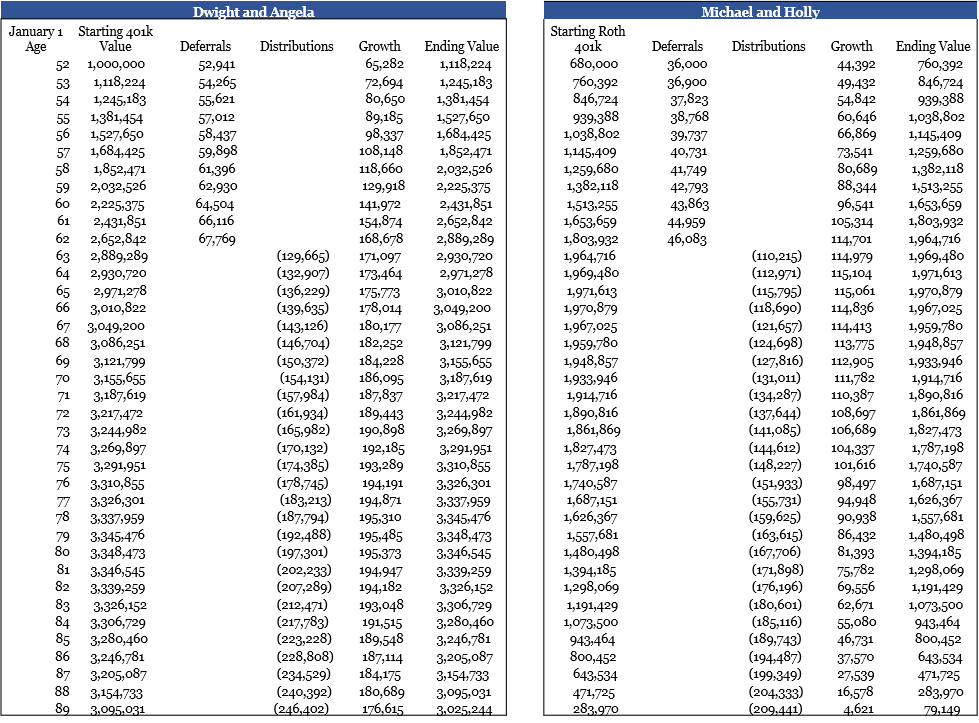

Consider the example of Michael and Holly, both 52-year old executives, married to one another and at the peak of their respective careers. Together, they earn $400,000 annually between salaries and bonuses Further assume that Michael and Holly continue saving at the same rate over the remainder of their work lives (adjusted for inflation[iii]), earn 6.2% per year on their investments, and then need to withdraw $7,000 each month for spending once they retire ($84,000 per year, in today’s dollars). They will have approximately $1.96 million combined in their Roth 401(k) accounts when they retire and will spend down the funds to cover their annual expenses, winding up with just $79,149 remaining on their 90th birthday. Now consider what would have happened had Michael and Holly instead lived an identical life in every way but instead of saving towards their Roth 401(k) account, they save to a Traditional 401(k) account. To make keeping score easier in this nearly identical scenario, we’ll use a new couple named Dwight and Angela where all the same assumptions apply except the retirement account type. By saving to their Traditional 401(k) accounts instead of a Roth 401(k), Dwight and Angela receive an immediate tax-deduction on the deferred funds that comes with the expense of paying taxes in the future when they distribute funds from the 401(k). Because they get the immediate deduction on 401(k) contributions, Dwight and Angela can effectively save more dollars now. This is to say that Dwight and Angela get to the same after-tax dollars available for spending by deferring a combined $52,941 to their Traditional 401(k) accounts versus the $36,000 that Michael and Holly saved to their Roth 401(k) accounts[iv]. After diligently saving to their Traditional 401(k) accounts for 11 years, Dwight and Angela enter retirement on the same day as Michael and Holly with just over $2,785,006 saved. But unlike Michael and Holly, Dwight and Angela cannot just distribute only the funds they need to spend as each dollar withdrawn from their 401(k) accounts is taxable income and creates additional taxes. To get $84,000 of net spending cash, Dwight and Angela must distribute $98,824 – $14,824 for taxes and $84,000 to spend[v]. When they reach age 90 – maintaining all the same variables as the earlier example – Dwight and Angela have a combined $3,025,244 remaining in their 401(k) accounts[vi]. It isn’t even close. At age 90, Dwight and Angela end up with $3.0 million combined in their pre-tax retirement accounts. Michael and Holly wind up with $0.08 million combined in their Roth 401(k) accounts. To get to a fair apples-to-apples comparison, Dwight and Angela’s $3.0 million needs to be taxed. But even if we assume that every dollar faces 37% tax rate upon distribution, Dwight and Angela still net $1,905,904 compared to the $79,149 of Michael and Holly. What creates the huge win for Dwight and Angela? The simple economics that they defer taxes now at a marginal rate of 32% and distribute funds during retirement at a significantly lower tax rate. Conversely, Michael and Holly do just the opposite – pay taxes now at a high rate to avoid taxes in the future at a lower rate. For Michael and Holly, contributing to the Roth in their peak earning years is the financial equivalent of choosing to pay $100 for an item with free shipping when they could buy the same item for $65 plus an added $10 shipping fee. There is an important mathematical reality that often gets missed when evaluating tax-free Roth accounts and tax-deferred Traditional accounts: if your marginal tax rate remains constant throughout life, then you are indifferent between using a tax-free account and a tax-deferred account. The result is the same. Assume that you face a constant 30% marginal tax rate over the course of your life. Consider what happens if you have $10,000 of pre-tax income this year and you elect to defer it to a Roth 401k account that grows at 8% per year for the next 10 years. You net $7,000 after paying the 30% tax, put the $7,000 in a Roth 401(k) account and let it grow at 8% per year for 10 years. After 10 years, you wind up with $16,321 to spend. Alternatively, assume you make the same $10,000 and put it in a pre-tax 401(k) account. It grows at 8% over 10 years to $23,316, you take it out and pay taxes at 30% of $6,995. Your net result is the exact same $16,321[vii]. But what if you have an incredible investment that will grow at 40% per year for the next decade. Certainly, you’d rather have that growth occur in a tax-free Roth account, right? No. Again, the same result: you wind up with $283,470 to spend regardless of whether using the Roth account or the Traditional account. All else equal, what matters in the comparison of deferring to a Roth 401(k) versus a Traditional 401(k) is simply your marginal tax rate now versus your expected marginal tax rate when dollars are distributed. Provided these tax rates are the same, you are financially indifferent between the options. Most successful individuals encounter a materially lower tax rate in retirement when they’re distributing funds from 401(k) plans and other retirement accounts. In our experience of counselling clients into retirement, it is extremely rare that anyone transitions from peak earning years to a higher tax rate in retirement. This typically only occurs when there is a large deferred compensation or severance payment in the first year(s) of retirement. In these cases, the higher tax rate is only temporary such that when the retiree begins drawing from a 401(k) account, the marginal tax rate is notably lower than the pre-retirement tax rate. Occasionally, clients retire into a higher tax state than they worked in but the reduction in federal rates more than offsets the increase in state tax rates. That said, we have yet to experience a real-life situation where a client would have been better off by contributing to a Roth 401(k) instead of a Traditional 401(k) during his/her high earning years[viii]. Now, the occasional push-back on this advice is: what happens if/when statutory tax brackets go up in the future? This possibility is difficult to handicap. Yet what we can say is that federal tax rates would have to go up dramatically for the tax-free Roth to make sense for successful mid- and late-career professionals in their peak earning years. In the examples above, the lowest tax rates would need to increase from 10% and 12% to nearly triple those levels for Michael and Holly to come out ahead. It’s not hard to envision a change where the 10% and 12% brackets go to 15% but it is really hard to envision a scenario where the 10% and 12% brackets go to 35%. One more argument against favoring tax-free Roth 401(k) deferrals, in case the economic case was not adequate[ix]. Consider two binary retirement outcomes. In the first, you are extremely wealthy in retirement. Perhaps you received an enormous inheritance, made tens of millions in employee stock options, or developed and patented some new widget that made millions. In the second of the binary outcomes, you are far less financially successful. Perhaps you had to retire earlier than planned or faced large unexpected expenses that consumed significant wealth. As a result, you are trying to make retirement work with less assets and income than you had planned. It goes without saying that we would all prefer the first scenario. But much of financial planning is about minimizing the probability and/or severity of bad outcomes. If you knew with absolute certainty at age 40 that you would wind up in the wildly successful first scenario thirty years later, then you would be wise to make Roth contributions during your working years (since, you’re worth tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in retirement and likely in a high tax bracket). Conversely, if you knew with absolute certainty at age 40 that you would up in the less desirable second scenario during retirement, you would be wise to make tax-deductible 401(k) contributions during your working years (better to get the tax deduction and accumulate more dollars of wealth in a 401(k) while you’re working since you’re likely distributing funds in a zero or near zero tax bracket during retirement). Effectively, tax-deductible 401(k) contributions provide insurance against the undesirable of these binary outcomes. So, if one goal of planning is to minimize the severity of bad outcomes, then favoring Traditional 401(k) accounts is a reasonable form of hedging without dramatic cost. This should not be the defining reason to favor tax-deductible 401(k) contributions during the peak earning years but at least adds one justification for this course. All of this is to suggest that the next time you consider getting a tattoo just because its free tattoo day, think about the actual cost of free. And the next time you think about making Roth 401(k) deferrals just because the Roth is tax-free, again consider the actual cost of free. [i] Assumes that they live in a state with no income taxes, have no additional taxable income sources, no other investment accounts, and take the standard deduction on their federal return. As a result, they face a current marginal tax rate of 32%. [ii] They are allowed to each contribute $25,000 to a Roth 401(k) in 2019 but high expenses prevent this level of saving. [iii] Inflation of 2.5% assumed for both savings and spending. It is further assumed that tax brackets increase at the same 2.5% rate. [iv] In addition, it is assumed that Dwight and Angela start with $1,000,000 in their 401k since this presents an equal comparison to the $680,000 post-tax amount that Michael and Holly have in their Roth account. [v] Note that the $84,000 is just an example. Because of inflation, the year 11 spending need for Michael and Holly is actually $110,215. Angela and Dwight need to distribute $129,665 to net the same value. A 15% blended tax rate is assumed here. Most of Angela and Dwight’s income would be subject to the 10% and 12% brackets with only a small piece subject to the 22% rate. [vi] Dwight and Angela would face required minimum distributions (RMDs) starting at age 70.5 but the distribution rate here (starting at $84k, inflation adjusted) has intentionally been set to exceed the RMD in all years to remove this factor. [vii] Not addressed here is the fact that Roth IRA accounts do not presently face required minimum distributions (RMDs) whereas Roth 401k accounts, Traditional 401k accounts, and Traditional IRA accounts all face the same RMDs. There can be a financial advantage to converting the Roth 401k to a Roth IRA before age 70.5 and avoiding RMDs. However, this advantage seems likely to be short-lived as Congressional legislation has proposed syncing the RMD rules and ending this Roth IRA loophole. [viii] In fairness, this ignores the dynamic I addressed here a few years ago that effectively allows someone to defer more dollars to a Roth 401k than a Traditional 401k. [ix] Credit here to friend and fellow advisor, David Hultstrom of Financial Architects, for the introduction of this useful binary outcome approach.

Who makes out better – Dwight and Angela or Michael and Holly?

Why are pre-tax 401k contributions almost always far better for mid and late-career professionals?

Final thoughts

Leave A Comment