Imagine walking into your new doctor’s office for a routine physical. The doctor asks for no information other than your age. From just that piece of information, the doctor gives you a clean bill of health, suggests that you exercise 3 times each week, eat a well-balanced diet, thanks you for coming, and reminds you to schedule another appointment in a year.

That is clearly a far-fetched hypothetical but it is actually not that different from the way much financial advice is given. Take, for example, the question of appropriate asset allocation. Many address this issue by referring back to a commonly cited rule of thumb which recommends using your age as the percentage of your portfolio that should be invested in bonds, while keeping the remainder in stocks. A 40-year old, using this logic, would hold 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, slowly reducing the stock exposure each year. The value of this rule is in its simplicity. “When there are multiple solutions to a problem”, investment legend Jack Bogle says, “choose the simplest one.”

But how confident would you be in a doctor’s advice if she merely asked for your age and then applied a rule of thumb to diagnose your condition and treatment? There is clearly a more tailored and effective way to think about the appropriate asset allocation dilemma than this one-size-fits-all financial advice.

The common rationale for this rule-of-thumb approach to portfolio risk is that a person should generally start with high risk early in life when the time horizon is long and gradually reduce risk to reach a relatively conservative allocation by the time retirement commences. The next question should be “why?”. Why can or should a 30-year old take more portfolio risk than a 60-year old? It is not simply about risk tolerance or proximity to distribution phase. Many individuals providing this advice would likely fail to have a sensible answer.

Rule of Thumb Dismissed by 2nd Grade Math

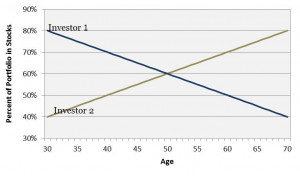

Students in 2nd grade are taught about the commutative property of addition and multiplication. The property states that if you are adding or multiplying several numbers together, it does not matter the order in which they come. The same principle applies to investment returns. Take two 30-year old investors with $250,000 to invest and no expected contributions or withdrawals over the next 40 years. Investor 1 starts with an 80% allocation to stocks and reduces that by 1% each year to get to a 40% allocation to stocks at age 70. Alternatively, investor 2 starts at age 30 with a 40% allocation to stocks and increases that by 1% each year to get to an 80% allocation to stocks at age 70.

Investor 2’s approach clearly defies the common approach of reducing risk over time. But the ex-ante expected portfolio values of these two investors at age 70 is identical. From a mathematical standpoint that ignores taxes, there is no difference in the approaches and no advantage to starting more aggressively. In fact, if you consider the likely tax impact of these approaches and investor 1’s tax cost of rebalancing to a more conservative allocation over time, the backwards approach of investor 2 is likely optimal because it results in fewer taxes in the early years (rebalancing happens without as much trading as stocks appreciate faster than bonds).

The truism of mathematics is that going from an aggressive allocation to a more conservative allocation does not reduce risk versus the alternative above. Investor 1 and investor 2 will have the same expected ending value and the same range of outcomes. Moreover, a new investor 3 who applies a constant 60% stock/40% bond allocation throughout the entire 40 years will also have the same expected end value at age 60. It appears that something taught in 2nd grade math dispels one of the most commonly cited financial rules of thumb.

Asset Allocation Through a Broader Lens

The classic age-based rule that leads to starting with an aggressive investment allocation and gradually becoming more conservative as retirement approaches is not entirely wrong. It tends to result in an appropriate solution more often than not, even if for the wrong reasons. However, it helps for a doctor to provide a well-rationed explanation for her diagnosis and it helps for financial advice to have a well-rationed explanation for asset allocation advice.

Examining this question through a broader lens aids in understanding why the gradual reduction of portfolio risk is appropriate for most investors. The key is that most individuals have not only financial capital (investment assets, for example) but also human capital. Financial capital is easily measured and understandable. In the earlier example, investors 1 and 2 started with $250,000 of financial capital. But these investors also maintain human capital – the inherent economic value that comes from their abilities to perform valuable services or labor over the course of their working lives. Human capital is more challenging to calculate because of the uncertainty of future salary, job changes, bonuses, and even the discount rate but it simply equates to the present value of an individual’s future earnings.

The illustration below offers a typical example of these two forms of capital where the blue line represents human capital and the gold line represents financial capital. In this example, the individual at age 25 has roughly $4.5 million of human capital but very limited financial capital. As he gets older, human capital declines (income is earned and either spent or saved) while financial capital increases up until retirement at age 60.

Now think about this from an asset allocation perspective. Human capital varies depending on education or skill but is typically far more bond-like than stock-like. There are some occupations where human capital behaves more like a stock but for most well-trained and educated individuals, aggregate earnings potential (lifetime human capital) is unlikely to rise or fall dramatically over a short time period.

In an uninformed context, allocating 100% of financial capital to stocks at any age may seem aggressive. But consider the illustration above where the individual is 40 years old and in a relatively stable career. The bond-like human capital of $3.4 million far outweighs the aggressively allocated financial capital of $187k. As a result, the combined asset allocation is still extremely conservative, even if the financial capital is invested entirely in stocks.

Closing Comments

Thinking about asset allocation in this broader context leads to far-improved decisions about the investment allocation. It also benefits by instilling confidence in the investor who understands the logic and informed decision-making used to develop an asset allocation. The decision is no longer just about age, proximity to retirement, and risk tolerance. Those things matter but they can ignore a huge piece of the puzzle in much the same way that a doctor failing to take a blood sample can ignore an important decision-making factor. What should become clear for any investor is that human capital, both it’s bond-like or stock-like risk and its relative proportion to financial assets, are hugely important in deciding upon an appropriate asset allocation for the financial assets. Two investors with the same age, same retirement date, and same risk tolerance would likely be prescribed the same asset allocation by many financial advisors but, depending on their human capital may need entirely different financial allocations.