German, Brazilian, English, Argentine, and Spanish football fans, take heart. Football (or in American vernacular – soccer) is quantifiably the least predictable major sport. In no other sport is luck such a critical determinant of the outcome. So you have that going for you the next time you sit down with a Frenchman to discuss football (soccer).

Consider that each team averages only a dozen shots per game, more than half of games are decided by a single goal, and the most common score in professional soccer is 1-0. A bad bounce or a fluke play determines many a game. And despite the luck-ridden nature of the sport, the World Cup doesn’t use a best-of-seven or a best-of-five series to determine the winner of each round. Teams play one game and the loser goes home to wait four more years for their next shot.

The frequency at which grown men fake severe injuries in the course of World Cup play should also demonstrate the hugely critical role of fouls in these low scoring affairs. Yet soccer uses only one referee to cover a playing area that is more than 16 times the size of an NBA court. To make matters worse, 1/3 of games in the knock-out stage during the last two World Cups ended in a tie and were decided by the most chance-laden contest of any modern sport – the penalty shoot-out.

Given all of this, it should be no wonder that soccer is the least predictable major sport. Favorites in college football win 75% of the time, 70% of the time in the NBA and NFL, and 60% of major league baseball games. In soccer, the favorite team barely wins half the time.

Understandably, this may provide little solace for fans of the afore mentioned teams who had such high hopes four weeks ago and now must wait four years for another shot at the next World Cup.

At least there may be good reason to remain hopeful for 2022.

Beware of Small Sample Size

One of the first things taught in a statistics class is that when the sample size is small, there will be greater variability of results and, resultantly, more unexpected outcomes. Flip a coin four times and the probability that you get three of either heads or tails is greater (50%) than the probability of splitting heads and tails (37.5%). Flip a coin 10,000 times and you will almost assuredly get between 49% and 51% of both heads and tails. If the 2018 World Cup were played 10,000 times and the country with the most victories claims the title, then the French probably aren’t celebrating this week.

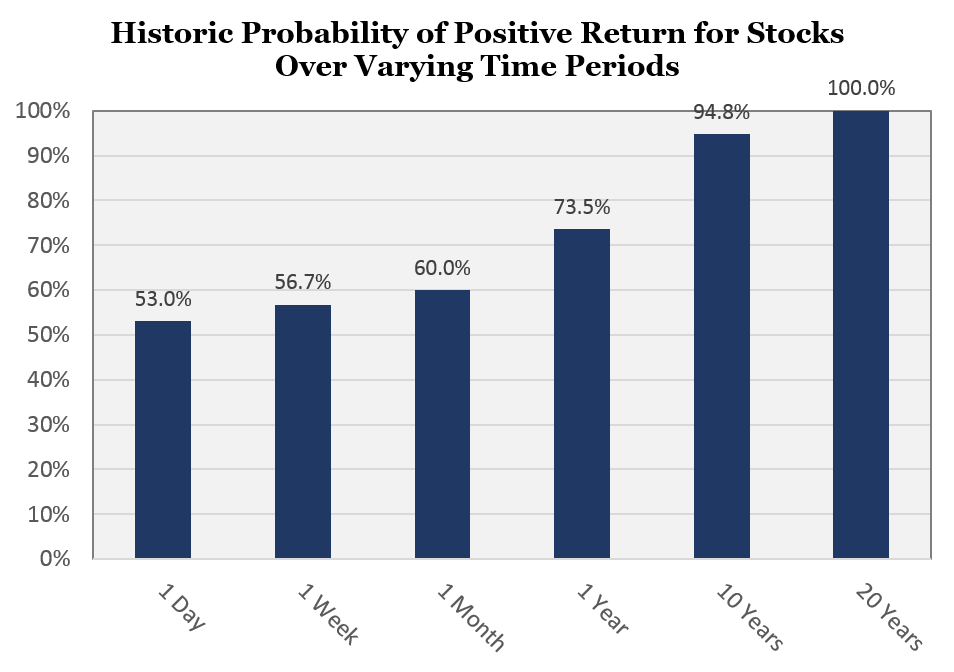

In investing, sample size is time. The shorter the time periods, the more variability in results and the more unpredictable the outcomes. Over long time periods, results tend to converge on their expected outcomes.

Consider investing in stocks. You should expect a positive return from owning stocks to compensate for the risk of owning them. But pick any random day from history and there’s a 47.0% chance that you lost money investing in stocks. Pick a random week and there is still a 43.3% that you are worse off on Friday afternoon than where you started on Monday morning. But take any historical ten-year period and the chances of a negative return plummet to 5.2%.

High Probability Events Are Not Certainties

According to FiveThirtyEight, Brazil entered the 2014 World Cup as the prohibitive favorite with an unprecedented 45% win-probability. They lost in the semifinals. Entering this year’s Cup, prediction models indicated there was a 60% chance that one of Germany, Brazil, or Spain would win. Only one of these countries made it to the quarterfinals and none to the semifinals. Which is again to say that the World Cup is highly unpredictable.

And so is investing. Even high probability tendencies are not sure things.

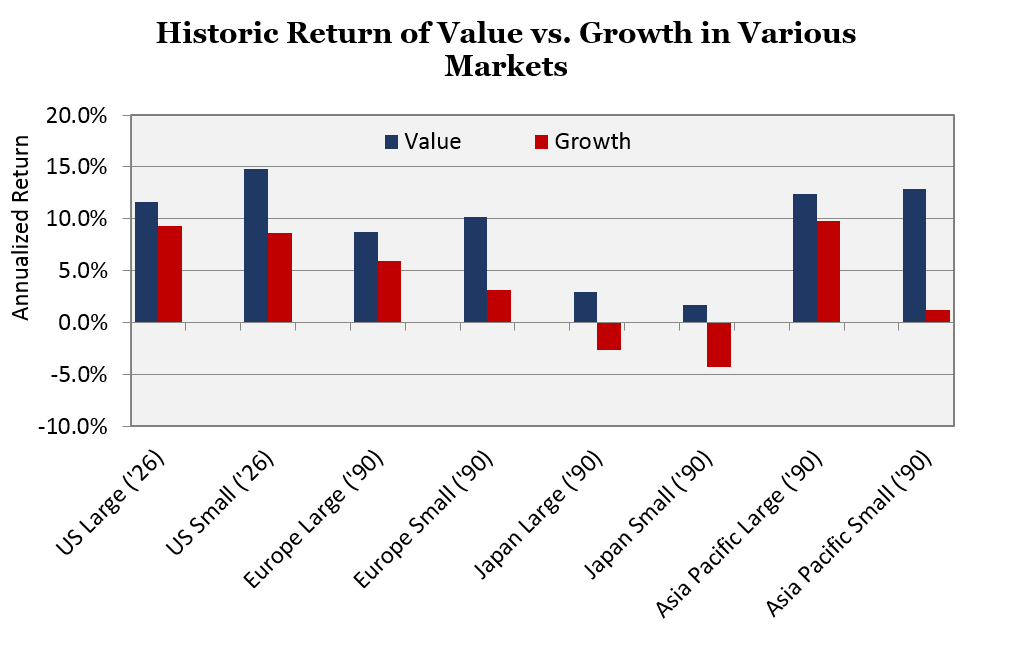

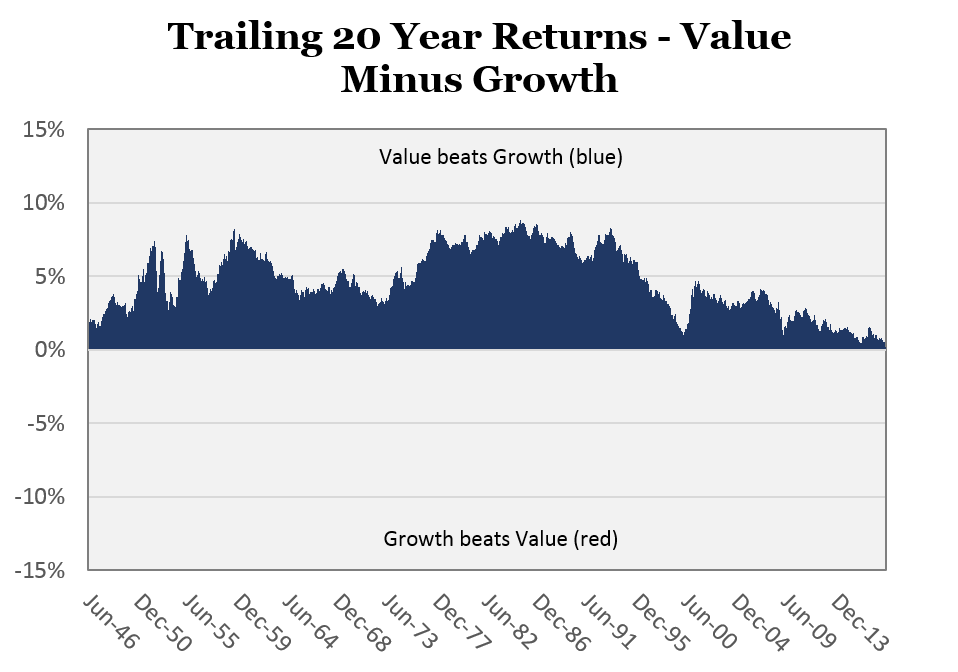

If there is any reliable tendency of the stock market, it is the expected long-term return premium of value stocks over growth stocks. This is to say that buying a diversified basket of cheap, unexciting stocks historically beats buying exciting stocks over long periods of time. The evidence on this phenomenon is robust, pervasive, and persistent. Pick any extended time period in any market and there’s a high probability that value investing will beat growth investing.

Value stocks are defined as companies like Colgate-Palmolive, Campbell Soup, and Hanesbrands that sell boring, low-growth, low margin products like dish soap, toothpaste, chicken noodle soup, and underwear. As a result of their lower growth and/or lower margin businesses, they sell at cheaper valuations. Growth stocks, alternatively, are companies such as Netflix, Apple, Amazon, and Google. Think exciting stories with trendy, high-tech products and popularity among millennials.

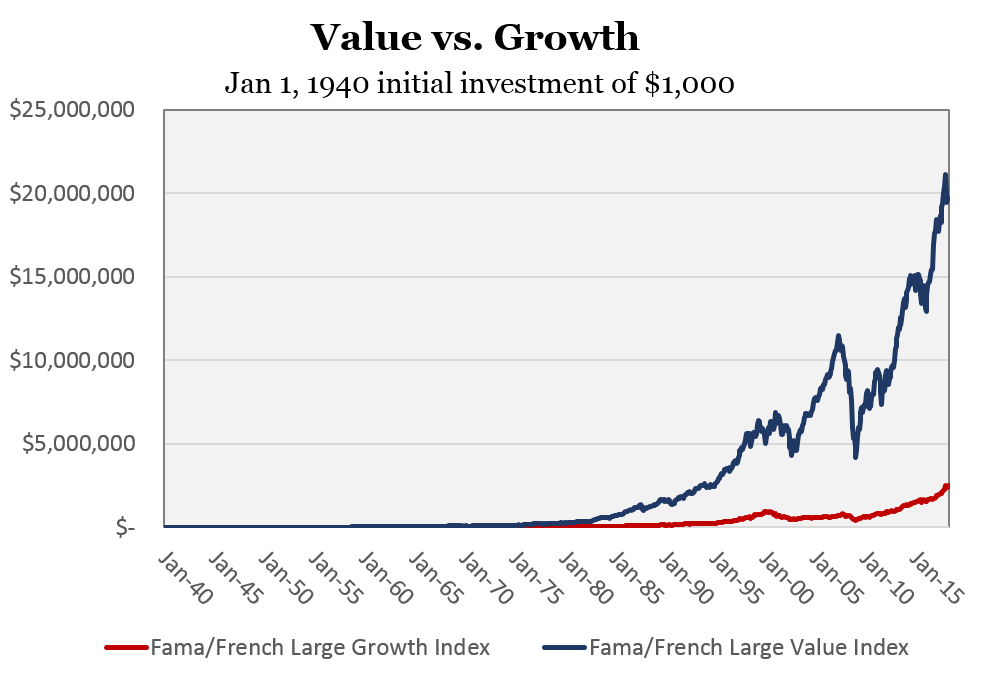

Most investors get far more excited about the second group of stocks than the first. And that’s a big part of why the story plays out as it does. Historical evidence shows that value stocks consistently beat growth stocks by a wide margin. Since 1940, value stocks have delivered a 13.4% annual return compared to 10.5% for growth stocks. Said differently, $1,000 invested in growth stocks in 1950 would be worth $2.5 million as of May 31, 2018. The same $1,000 invested in value stocks on January 1, 1950 would now be worth $19.7 million.

Why such dominance? The so-called ‘value premium’ can be explained by several factors – some related to the higher risk of value stocks and some tied to the irrational behavioral biases of humans.

Importantly, value stocks experience higher volatility of metrics like dividends and earnings which inherently make them riskier. Higher risk means higher returns. Additionally, investors tend to consistently overestimate the persistence of growth for high growth companies and underestimate the ability of companies with depressed expectations to exceed those expectations. As a result, growth stocks often fail to live up to the implied expectations (which means they tend to be overpriced) and value stocks often tend to exceed the lowball expectations (which means they tend to be underpriced).

Value investing also owes some of its success to the lottery preference of human brains – an inherent behavioral desire we have to prefer long-shots at the racetrack or an exciting technology company with the small potential of a 20x return. Investors, as a result, pay more than they should for trendy growth stories or 100-1 race horses which, conversely, drives down their expected return. All these factors and others cause growth companies, in aggregate, to be overpriced relative to their intrinsic value and value companies to be underpriced.

The Four Most Dangerous Words in Investing: This Time is Different

None of this is to say that growth will always lag value over extended time periods. It is just to say that the increased risk of value stocks and the behavioral biases of humans to explain the tendency coupled with the empirical evidence suggest that value stocks are likely to “win” over most extended time periods.

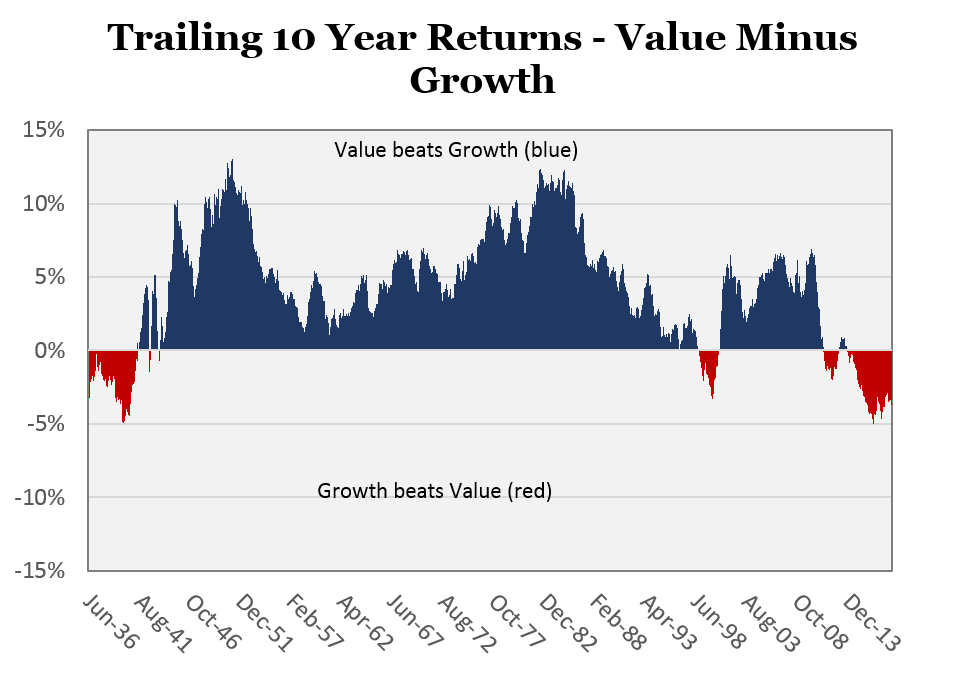

Most, but certainly not all. In fact, while value investing has yielded far better returns than growth investing over many decades, there are long stretches where growth “wins”. One of those win streaks is ongoing. Since the peak of the stock market in 2007 prior to the financial crisis, growth stocks have been the place to be – led by the technology sector and well-known tech giants like Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. Over the past decade ending June 30, 2018, the Russell 1000 Value Index has returned 8.5% versus 11.2% for the Russell 1000 Growth Index. And it is not just in the United States that growth stocks are outperforming value stocks – the same trend is true over the past decade in nearly all global stock markets.

Only during the irrational exuberance of the dot-com bubble and during the Great Depression have value stocks lagged growth stocks by this degree.

Are things different this time and value investing is now broken? Such arguments were made in the late 1990’s – that the Internet would reshape our economy and value sectors such as energy, consumer durables, financials, and basic materials were dying. These prophecies were obviously laid to rest during the dot-com bust. Again today, we do not believe that the value premium is a thing of the past.

The market, in our opinion, is simply going through another extended period where growth stocks are in favor. It happens. Even though robust evidence suggests that value stocks outperform growth stocks over time, it does not occur in all environments.

All this said, we feel strongly about a few things:

1) Determining when market leadership will change is difficult, if not impossible. There are plenty of possible catalysts for a market reversion back to favoring value stocks – rising interest rates, financial deregulation, higher oil prices, or a slowdown in consumer spending, to name a few. Trying to predict how long the growth-favored environment lasts is not a productive endeavor.

2) Growth stocks are expensive relative to their historical standards and have lofty expectations that may be difficult to achieve. Expensive valuations do not necessitate an immediate reversal but they are usually a sign of below-average returns for the following decade.

3) The long-term outperformance of value stocks across the globe is probably the most robust and most well-researched of all investment phenomena. There are strong explanations for its existence over the past century that are unlikely to change.

Closing Comments

The World Cup is unpredictable. Investing is unpredictable. Yet the huge advantage of being a patient investor as opposed to being a patient soccer fan is that you eventually have the advantage of probabilities and results converging. A 50-year old English soccer fan has only had 13 shots at the World Cup and despite some great teams and strong chances, has yet to experience a World Cup championship. These things happen when the sample size is small. Probabilities and results don’t always line up.

Investing in stocks will occasionally entail long periods of negative returns. That’s been true before and is likely to be true again. The same can be said of tilting a portfolio of stocks toward value. There will be periods when such investments aren’t in favor but the beauty of disciplined investing is that time is your friend. Expanding your sample size tends to the convergence of expected outcomes and results.

Leave A Comment