My recently turned 5-year old son began playing chess over a year ago and it has been instructive to see his approach to the game develop. Immediately recognizing the importance of the queen, he developed a foundational strategy that revolved around that piece — establishing his own pieces to capture the opposition’s queen early in the game while concurrently protecting his own queen. Experienced chess players will likely agree that this strategy can be useful but if applied indiscriminately to all situations, it is decisively sub-optimal.

The flaw of this strategy is not necessarily that it is a bad means of addressing some situations, but that it is a bad means of addressing any and all situations. There is meaningful strategic benefit to considering the big picture and the relative importance of all the pieces in the game of chess.

This same big picture thinking offers an instructive lesson for investing. Around the midpoint of the 20th century, the eponymous “income approach” served as the foundation for portfolio construction. Investors allocated to different varieties of bonds, dividend stocks, and preferred stocks to achieve enough income from the portfolio that they would not need to invade the principal. At the time, using a collection of income-oriented investments to support cash flow needs was good enough. Yields were significantly higher and the prevailing knowledge knew no better.

Nobel Prize research in the 1950s inspired institutional investors to think differently and abandon the artificial definitions of principal and income. As with a big picture approach to chess, “total return” investing offered a far more optimal approach and was widely accepted by sophisticated investors. This new approach considered all potential sources of return, including cash flow and capital appreciation, recognizing the merits and drawbacks of both. Rather than let the investments dictate where the necessary cash flow was produced, total return investing created a synthetic dividend. Eventually, ERISA and the Uniform Prudent Investment Act began to require the total return approach as there was a common understanding that the income approach was inefficient.

Despite the long-standing acceptance of total return investing among institutional investors, there is still an inherent desire of retirees to have portfolios that deliver income. The retail marketplace, resultantly, caters to this old-school thinking and provides yield-oriented products or dividend focused funds because they easily sell to investors clinging to an income approach. In the current low interest rate environment, demand for such investment styles has intensified and the industry has accommodated to the demand. The income approach, however, has several critical drawbacks regardless of the interest rate environment.

Drawbacks of the Income Approach

1) Limits Opportunity Set. The income approach focuses on one metric (dividend yield) while largely ignoring all others (valuation, quality, cash flow yield, fees, risk, etc.). In the simple case of stocks, the approach eliminates from consideration all stocks that do not pay a dividend. It ignores investments like commodities and gold without any income. It irrationally penalizes corporate executives who deem that a better use of cash is to buy back stock or reinvest in the business. Conversely, buying stocks based on a non-guaranteed dividend yield without factoring in other measures like the cash flow yield or the payout ratio artificially rewards companies based on a single inappropriate metric. Simply put, applying an income approach means unnecessarily limiting the opportunity set of investments.

2) Ignores Inflation. Assuming other flaws could be mitigated, the concept of producing enough income to cover expenses appears naïvely valuable in practice. One could build a portfolio of income producing assets and live off the income payments each month. However, without appreciation of principal, the income quickly fails to keep pace with inflation. At a 3.5% inflation rate, 100 dollars of consistent income will buy less than $60 worth of goods and services in just 15 years. Longevity risk and inflation risk represent two of the most significant financial risks that a retiree faces. A strict application of the income approach elevates these risks, potentially forcing an unprepared future reduction in lifestyle.

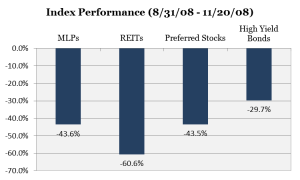

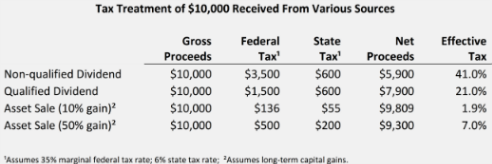

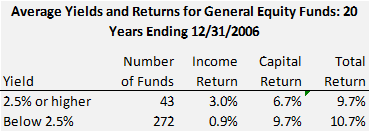

3) Forces Allocation to be Dictated by Spending. A diversified portfolio of 50% bonds and 50% stocks currently pays a yield of 2.23% a) Increase credit risk by adding junk bonds, real estate (REITs), emerging market debt, master limited partnerships (MLPs), etc. b) Increase interest rate risk by buying longer duration investments such as 30 year bonds, utility stocks, preferred stocks, etc. Both of these options expose the retiree to greater risk of principal loss and essentially exchange higher current income for the risk of significantly lower future income. Investors who bought yield-heavy investments like REITs and MLPs or who replaced investment-grade fixed income with high yield bonds experienced this risk of loss during the heart of the financial crisis[ii]. 4) Highly Correlated Portfolio. Modern Portfolio Theory postulates that the one free lunch in investing is diversification. That is, properly diversifying risks reduces portfolio volatility without sacrificing return. The income approach, however, tends to disregard this free lunch by covertly concentrating the same risks. An investor who builds a seemingly diversified portfolio of utility stocks, preferred stocks, and long duration muni bonds to generate additional yield is likely to see these assets all move in unison – all suffering losses if interest rates move higher. Instead of benefitting from the diversification of risks, an income approach can concentrate risks and lead to unnecessary volatility. 5) Tax Inefficient. While taxation on qualified dividends became more investor friendly in 2003 following the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act, the idea that dividends and capital gains are on a level playing field is misguided. While the 15% tax rates are equal, the amounts that the tax is applied to are not. The table below provides an example of the more onerous tax rate on dividends and income. 6) Ineffective Investment Approach. Defendants of an income strategy will argue that dividend stocks historically outperform non-dividend stocks. There is conflicting evidence on the accuracy of this argument. A study done by Lipper of 20-year returns found that lower yielding equity funds significantly outperformed higher yielding funds. It can be argued that dividend stocks outperform over certain time periods but this ignores what is responsible for the higher returns. Cheaper stocks (“value stocks”) tend to outperform over long periods and many, but not all, dividend stocks benefit from this value premium. Remove the value premium and there is a lack of compelling evidence that dividend stocks outperform over any extended time periods. There is also no useful explanation for why they should outperform as no benefit is created by a dividend payout. The fundamental underpinning of total return investing is that it distinguishes the need for cash from the need for income. Consider the difference. Many retirees think they need income and the marketplace is very willing to promote this old-school thinking. However, what they really need is cash. As an analogy, think about the means of keeping your grass green in the summer. You could elect to rely solely on rain which would work adequately in some years. But just as it is not income that a retiree needs, it is not rain that your lawn needs. It is water. As a result, most families interested in maintaining a green lawn during the summer months employ a total return approach to lawn care. They create a synthetic water dividend by strategically combining some combination of rain, sprinklers and manual hosing. The total return approach offers a more optimal approach to investing by providing the same synthetic dividend. This approach does not mean ignoring dividend stocks or income investments. It means including this income as part of the equation but not strictly relying on these sources to produce the necessary cash flow. As a result, investors end up with the equivalent of a healthier investment lawn with just a little extra maintenance.Closing Comments

Leave A Comment