Few things in our profession are more frustrating than when financial advisors deliver bad financial advice. It doesn’t have to be that bad financial advice is dishonest or delivered for the wrong reasons (like it is so often, for the benefit of the advice-provider). It is just that misguided or blatantly wrong financial advice hurts consumers and degrades our profession. So, when a client recently forwarded me a terribly misleading article from our local newspaper about dividend investing, I was forced to respond.

The purpose for responding was not to target the author (whose work is generally quite good) as ill-intentioned. The point was simply to dispel faulty assumptions and to fundamentally challenge the advice or conclusions. I wrote back, “Candidly, the author makes several statements that are not true and he argues points that, if taken to conclusion, would actually argue against owning dividend stocks.”

The following is an expanded version of my response to the article, breaking up the original article into word-for-word statements (below, in bold) and then commenting on them.

“Most investors hone in on just the growth piece of the equation, and give little thought to the income piece.”

Actually, just the opposite. The data actually indicates that most investors have focused too much on income in the low rate environment of the past two decades. Yield-starved investors have been chasing yield for the better part of the past decade. Dollars have flooded into utilities and telecoms that pay high yields, REITs, preferred securities, high yield bonds, MLPs, and anything else with yield. This focus on income is accelerating by the day as more baby boomers retire and believe they need income to help pay bills. In fact, there are few periods in history where investors have focused less on income.

“But income is a crucial component to this equation, too. In fact, since 1929, dividends have accounted for 43 percent of the total S&P 500 return.”

Income is an important part of the total return equation for stocks and dividends have accounted for >40% of S&P 500 returns over time. Yet this information does not somehow imply that investors should focus on dividend paying stocks. It simply means that dividend interest is part of how companies reward shareholders. Don’t read more into it than that.

“As long as a dividend-paying company doesn’t hit a disastrous speed bump, chances are that they will continue to pay a measured level of income.”

Which is to say that as long as a company continues to do well, they will continue to do well. But if they don’t, then they won’t.

“Investing in dividend-paying stocks can give us a sense of predictability, thanks to the cash flow we receive from those shares. Of course, dividend payouts can change in a heartbeat if companies run into trouble.”

Summary: Dividend stocks provide a predictable cash flow until the companies run into trouble, in which case, the dividend is now unpredictable. This is again saying that things are predictable until they’re unpredictable which should not be a rational reason to invest in dividend stocks.

“However, many corporations place an enormous amount of importance on maintaining and even increasing their dividend payout over time.”

Very true – companies that pay dividends place a large importance on their dividends because cutting the dividend would be an unwelcome signal of stress to the market. But just because a company places an importance on the dividend does not provide any assurances that the dividend will continue. Consider the recent case of the nation’s largest pipeline operator, Kinder Morgan. Kinder Morgan paid a quarterly dividend that increased from $0.30/share in 2011 to $0.51/share in 2015. A decline in oil prices then led to deterioration of the business and management was forced to cut the dividend by 75%. This dividend cut came after the stock had already fallen 64% from $44 in April 2015 to $16 just eight months later. There are countless similar examples.

“In fact, there are many businesses that have paid dividends for more than 100 years without interruption, like the York Water Co., Church & Dwight, and General Mills. In a world full of uncertainty, finding companies with historically steady payouts helps us sleep better at night.”

Granted, there are companies that have paid uninterrupted dividends for over a century but that’s just a fact about the past. Eastman Kodak paid an uninterrupted dividend for over a century. Then it filed for bankruptcy. Other companies like Bethlehem Steel, General Motors, US Steel, Goodyear Tire and many others paid dividends for nearly a century before eventually filing for bankruptcy. Knowing that a company paid a consistent dividend for the past century tells us something about its past. It tells us very little about its future other than to suggest that the company doesn’t have productive uses for its cash in the business.

“Dividends can also be an indicator of a company’s financial health. As a wise money man once said, “Dividends don’t lie.””

Dividends are an indicator of health, not the indicator of health. When a a car dealer asks what kind of car you want, you don’t simply state that you want a blue car and leave it at that. You’re more likely to say you want a fuel-efficient, small SUV, with less than 30,000 miles, that rates high in safety and is blue.

Dividends matter but they have to be considered alongside many other metrics and data points.

“When a company pays a dividend, it’s proving that it has cash in the bank, which typically indicates a strong and solid balance sheet fueled by a good business model that generates steady and growing profits.”

The statement above should remind you of this 2011 Lending Tree commercial. Just because your neighbor drives a fancy car, has a nice home, and belongs to the country club does not mean his finances are healthy or his balance sheet is solid. Similarly, there are few impediments to stop an unhealthy, weak business from borrowing money to pay a dividend. In fact, many companies do as evidenced by this Wall Street Journal article.

“Dividend stocks can also replace income that investors once received from the matured bonds they owned to provide their portfolios with both stability and interest income. The interest rates paid by bonds have been sliding for many years. In 2016, more than 32 percent of S&P 500 stocks had dividend yields greater than the 10-Year U.S. Treasury Yield. Hence, the cash flow we receive from stocks could outpace that of traditionally higher-paying bonds.”

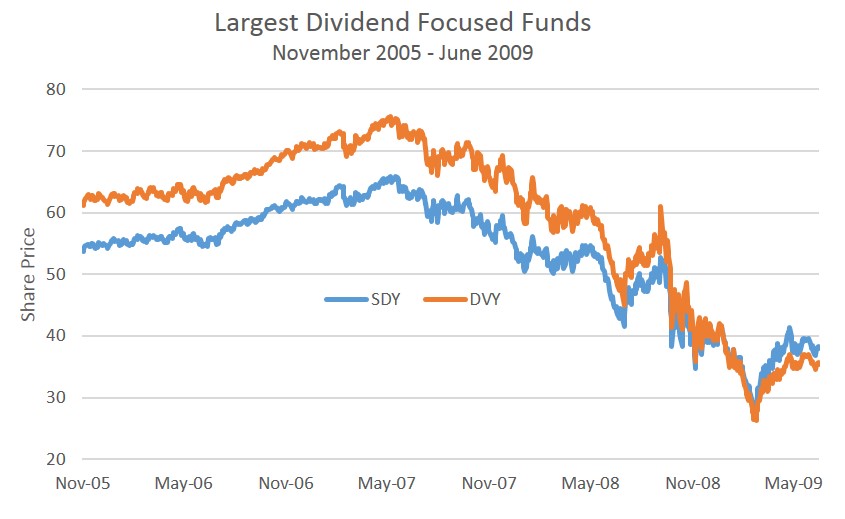

This is where the implied advice goes from misleading to dangerous. If you’re buying dividend stocks to replace high grade bonds, you’re definitively taking on more risk and getting the opposite of stability. Just consider the two largest dividend focused exchange traded funds: iShares Select Dividend (DVY) and SPDR S&P Dividend ETF (SDY). These funds lost 65% and 59% of their respective values between mid-2007 and March 2009. I don’t know investors for whom this type of “security” helps them sleep well at night.

Can you buy stocks that yield more than the 10-Year US Treasury’s current 2.3% yield? Absolutely. But it is nothing less than frightening when investment professionals imply that investors consider dividend stocks to replace the safe portion of their portfolio just because the yields are higher.

“Interestingly, dividends have lost favor in recent years as firms opt instead for stock buybacks under the theory that these two methods of rewarding shareholders are essentially equivalent. Stock buybacks happen when a company repurchases its own shares of stock at market value, and then reabsorbs ownership that was previously distributed among public and private investors. This inherently helps a company to increase its earnings per share, as there are less shares outstanding; however, it removes a major incentive for income investors to own these stocks.”

A company can give excess cash back to shareholders in two ways: buying back stock or paying a dividend. Both serve the same result in transferring money to shareholders. The dividend forces the shareholder to pay a tax. The buyback lets the shareholder decide if he/she wants to pay tax (by selling shares to create a dividend). The only reason a shareholder should favor the dividend (being forced to pay tax) is if he/she is just too lazy to sell the shares on his/her own. Suggesting that stock buybacks remove an incentive for investors to own such stocks is effectively saying that you should pay unnecessary and arbitrary taxes because your financial advisor is too lazy to sell shares of stock, as you need cash flow.

“The most obvious perk of dividends is cash-in-hand — that quarterly income payment. Buybacks, meanwhile, can result in the market placing a higher value on the company’s shares. A buyback may cost you income but potentially give you growth in the form of a higher share price. As an income investor, I’d rather have the dividends.”

Consider these two choices – you can either get $10,000 today and pay a tax in the future or get $10,000 today and pay an immediate tax. This advisor is indicating he prefers the latter. Wise investors, if given this choice, would choose the former without blinking.

If a company buys back stock so that your shares increase in value by $10,000, they’re giving you a reward and letting you choose when (if ever) to pay tax on this reward. Companies that instead pay the $10,000 dividend force you to immediately pay tax.

There’s a reason that Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has not paid a dividend since 1967. Dividends are tax-inefficient for Buffett’s shareholders and Buffett is keenly aware of this. Moreover, when he compares all the alternatives for free cash flow – buying other businesses, reducing debt, investing in existing businesses, buying back stocks – he admits that dividends are the least desirable option. Notably, Berkshire Hathaway paid a $0.10 dividend in 1967 to which Buffett later joked, “I must have been in the bathroom when the decision was made.”

“Here’s the cherry on top of my l-love-dividends sundae: Most dividend income is taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income. This is because most dividends that come from U.S. companies fall into the “qualified” dividend camp.”

True, but they’re taxed at the same rate as long-term capital gains. So this “cherry on top” argument is only an argument that stock dividends are better than bond interest – not an argument that dividend stocks are better than non-dividend paying stocks. If we’re comparing stocks to stocks, then this argument quickly dies and becomes an argument against dividend stocks.

The argument above is comparing that taxes of dividend stocks to bonds. While it is true that qualified dividends are taxed at a more favorable for most taxpayers than the ordinary income of bonds, that’s just entering again into the dangerous territory of comparing stocks to bonds.

Closing Thoughts

To be clear, none of this rebuttal is intended to leave the conclusion that investors should ignore dividends or that dividends are not important. Dividends have been an important component of equity returns in the past and they will be in the future. Instead, the case made here is that the idea of focusing a portfolio on dividends is misguided and that some of the justifications made for such an approach are deceptive. Quite simply, it is dangerous for anyone to suggest that investors use dividend paying stocks in lieu of safe bonds just because the yields are higher. While the idea of dividend paying stocks can be compelling to a retiree who is now without many income sources, the notions that dividend stocks provide “predictability” or that those companies that choose to pay dividends are in some way healthier than non-dividend payers are misleading.

The reality is that dividend-focused investing is less tax efficient than total return investing, has historically produced lower total returns than a broad value-oriented portfolio, leads to greater concentration, and has historically lead to greater risk. If you’re interested, we wrote this article a few years ago about income investing which explains these shortcomings in more detail. It also explains why institutional investors now use total return investing rather than the sub-optimal income approach and why you would be wise to do the same.

All that said, the final conclusion is simply this: beware of what you read or hear in the financial media. There’s a natural tendency to discredit what we don’t want to believe but we should be just as cynical when it comes to concepts that we may want to believe are true.

Leave A Comment