Spend any time working in the kitchen of a restaurant and you will think of restaurants very differently going forward. Following a short experience in a restaurant kitchen during college, I’ve never once sent a meal back for being undercooked, overcooked, or even the entirely wrong order. Use your imagination and we can just leave it at that.

Seeing how the proverbial sausage gets made often has a profound impact on future actions. Just ask anyone who has ever been part of the sausage making process.

While perhaps a little more glamorous than working in a restaurant kitchen or making sausage, the experience of trading several million dollars of bonds each week for a large institutional money manager provided a similarly eye-opening vantage.

I gained several important insights from this experience but most notable among them was the enormous exploitation of individual investors and the disadvantages they face. Bond traders know that individual investors are unsophisticated and they generally don’t have any reservations about getting rich off this knowledge. And keep in mind that when using the term ‘individual investors’, it is not merely describing some person occasionally buying bonds from the basement or home office. I’m also describing the exploitation of financial advisors at firms just like ours who are buying and selling bonds for their clients. These individuals and financial advisors are often completely oblivious to or dismissive of the huge disadvantage they face. In reality, they are often holding up a big sign that says “I’m here to buy your worst bonds at an outlandishly high price”.

You pay a huge price for individual bonds – and you have no idea.

If you go to buy a car and undertake in the price negotiation that is part of the process, there’s a theory that you should not wear expensive, fancy clothes. Better yet, wear raggedy clothes and look the part of someone who cares about the outlay of every single dollar. The theory suggests that you are signaling to the seller that you don’t have deep pockets which then puts you in a better position to haggle on price.

Investors would be wise to consider the effect of signaling when they’re buying or selling bonds. Consider, for example, what happens when you go to a broker (online or personal) to buy a $15,000 municipal bond lot. In this case, you’re holding that big sign that says “I’m here to buy your worst bonds…” Because of the size of the transaction, the seller immediately has a high degree of certainty that you don’t have access to a Bloomberg terminal, that you don’t have much knowledge of the bond terms, that you don’t know how much you should be paying, and that you are generally an unsophisticated buyer.

Large institutional investors with analysts who are evaluating the credit quality of the bond and have expensive Bloomberg terminals where they can see how the bond should be trading are not buying small $15,000 lots. They’re usually buying several million dollars at a time. As a result, bond dealers know a lot about the participants on the other side of the trade just from the size of the trade.

Unlike with large liquid stocks that trade millions of shares every day, many municipal bonds often only see only a few trades each month. This infrequent trading of municipal bonds provides a significant advantage for dealers in that it makes it very challenging for individual investors to know if they’re getting a fair price. The lack of transparency in the market just opens the door for bond brokers to charge small investors far more than they should be paying (or pay them less, in the case of a small investor selling to a broker). Additionally, individual investors provide an avenue for bond traders to dump the bonds that they can’t get rid of anywhere else. The underwriting bank might get stuck with $1 million of a bond that they can’t sell to institutional investors but they can carve it up into $10,000 and $20,000 lots and sell those pieces all day to individuals.

Trade data available online via the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) demonstrates the dramatic exploitation of small investors. We show one example below – a recent trade of a 20-year Fulton County (GA) Revenue Bond (12/30/15 issuance; 3.5% coupon; cusip 3599007A9).

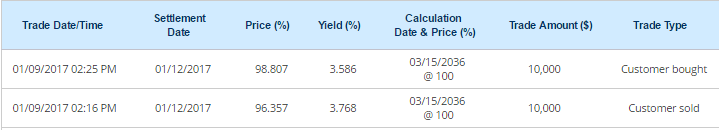

In this January 2017 transaction, a dealer purchases a $10,000 bond lot from a customer at $96.357 per bond. The dealer then immediately sells the same lot to an individual investor at $98.807. The investor here pays a spread of $2.45 per bond which amounts to a markup of more than 2.5%. Notably, this cost is hidden to the buyer. The buyer likely also pays a transparent $10 – $25 commission for the trade which he or she thinks is the cost of the transaction.

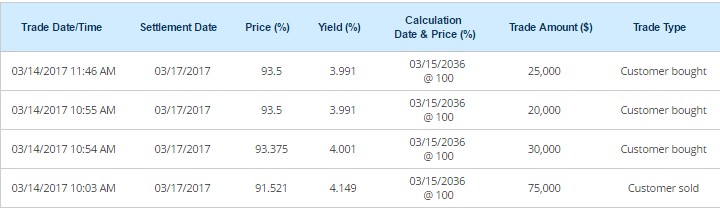

Below are the details for a more recent March 2017 trade of this same municipal bond. In this case, a broker buys 75,000 par value of the bond from one customer for $91.521 and then, within the next two hours, sells this bond in 20,000 – 30,000 lots to retail investors for $93.50 and $93.375 – again a markup of more than 2%. The bond dealer makes $1,447 – a transaction cost that is blindly paid by the individual buyers and sellers.

This is not unique. In fact, it is the norm. Individuals building portfolios of bonds using relatively small bond positions (<$100,000 lots) face these secretive hurdles. And in a world where high-grade, intermediate-term bonds yield 3-4%, paying a secretive commission of 2.5% to buy a bond presents an obviously huge cost for individual investors.

Maybe this is enough to convince individual investors to stop buying bonds on their own. But there are additional reasons why individual investors should generally not be building bond portfolios on their own.

It is easier to rebalance with bond funds.

If a mutual fund investor needs to raise cash or simply reduce the bond allocation, it’s fast and easy to sell units of a bond mutual fund or exchange traded fund. An investor with 10-25 bonds who needs to raise cash must determine which bond to sell, get quotes, evaluate whether the quotes are competitive, and then sell the bond. Depending on what bond the investor sells, the resulting duration or credit quality of the portfolio may now be significantly different than it was before.

Consider the real world. We have some clients who own a portfolio of bonds that they bought on their own or through another advisor. Occasionally, they need cash and ask for advice on which bond or bonds they should sell to raise cash. To respond to this question with an answer better than what a monkey throwing darts might provide, we need to at least know the intended duration and the targeted credit quality of the bond portfolio. But let’s be honest – the investor would have a big blank stare if we asked for the portfolio’s intended duration and credit quality. So maybe determining what individual bonds to sell is easier than we suggest. Just ask a monkey to throw darts at a list of holdings.

Let’s be honest again – a portfolio of individual bonds is not being effectively monitored.

An investor, either an individual or a financial advisor, buys a portfolio of A or AA rated bonds. This investor looks for available bonds with the highest yields, given the credit rating and the maturity. These bonds are purchased and the investor only takes further action if there is a significant credit rating change or a maturity.

This common process assumes that all bonds of the same credit quality are the same. They’re not. One need only read The Big Short to understand how flawed the credit rating process is and how little trust the significantly conflicted ratings merit. An A-rated bond yielding 4.0% is not necessarily a better deal than an A-rated bond yielding 3.7%. It is not a free lunch – the 4.0% bond is just riskier than its 3.7% peer. In good times, the higher yield just means a higher yield. However, in periods of economic weakness, the higher risk of the higher yielding bonds is more likely to result in downgrade or default. Within a portfolio of just 10-20 bonds, these events can have a dramatically negative impact on long-term results.

The other problem with this buy and hold process is that bond yields change as the bonds get closer to maturity. A 5-year municipal bond bought 4 years ago with a yield of 3.5% likely has a yield of around 1.0% or less today, with only a year remaining to maturity. Many individual investors erroneously think that if they hold the same bond, that the yield never changes because they’re receiving the same coupon payment. This flawed understanding of bonds poses another hurdle for individual investors who elect to buy individual bonds rather than a bond fund. What it means is that the return from these individual bonds may be fine in the years immediately after initial investment but is likely to be lousy as they approach maturity or call date. If the understanding of this math is not immediately clear, then that presents another good reason to avoid investing in individual bonds.

It is far easier to achieve diversification with bond funds.

It arguably requires at least 25 different bonds to achieve a healthy level of diversification. If you wisely limit bond purchases to lot sizes of no less than $50,000 to avoid the huge markups on smaller lots, then you mathematically need at least $1,250,000 in bonds to achieve suitable diversification. Of course, this $1.25 million in US high grade bonds is only part of a portfolio that would appropriately also include US stocks, foreign stocks, foreign bonds, high yield bonds, etc. The point is this – only investors with several million dollars to invest should be even considering individual bonds.

Bond funds provide more efficient reinvestment of coupon payments.

Bond mutual funds and exchange traded funds are efficiently able to reinvest coupon payments immediately. Investors with individual bond positions often have to wait several months or even years for enough coupon payments to accumulate before they can efficiently reinvest in another bond. Considering that uninvested cash represents a drag on long-term performance, funds help to minimize this drag relative to a portfolio of individual bonds.

Final Thoughts

The point of all this is simply to explain why most individual investors – and especially those with less than $1.5 million to invest in bonds or those who are trying to do the bond purchasing and selling by themselves – are far better served to use mutual funds or ETFs. Often times, investors have this notion that individual bonds are better to own because they’re cheaper or because they’ll get back their principal. Such notions are often ill-founded or just wrong. Yet, these misguided ideas are often promoted by bond traders who stand to make a lot more profits selling individual bonds than a bond fund or ETF. They might also be promoted because an advisor can justify a higher ongoing fee to buy 10-20 individual bonds than what he or she might justify by buying a single bond fund.

At the end of the day, there are legitimate reasons why a large investor might benefit from hiring a professional bond manager to put together a portfolio of individual corporate or municipal bonds. But let’s put an end to the phony, one-size-fits-all idea that this same logic applies to all investors. The reality is that most individual investors would be far better off owning a bond fund or ETF for all the reasons mentioned above.

I learned from this article. I was that guy: “…individual bonds are better to own because they’re cheaper or because they’ll get back their principal. Such notions are often ill-founded or just wrong.” If I buy bonds, they’ll be in a fund of some type.