Buckle up, America. Higher interest rates are coming. Forget that we have collectively observed this erroneous warning a dozen times or so over the past decade. We also had 13 Triple Crown attempts since Affirmed in 1978 and consider what happened recently to that lengthy streak of failed expectations.

For the first time since June 2006, the Federal Reserve looks primed to increase interest rates later this year or at least early in 2016. The warning bells are ringing like this one from Fox Business last week: “Lookout Retirees, Here Come Rising Interest Rates”. We are warned here to adjust our investment strategies and expect our “principles to drop”, which for the ethically conscious may be worse than if our bond principal were to drop.

The basic premise of these warning bells is that the Federal Reserve is going to raise interest rates which will hurt bond returns and so investors should reduce their bond allocation. Before taking cover and preparing for the impending period of rising interest rates, it is worth considering some of the faulty logic encouraging investment action.

Fallacy 1: Higher interest rates are coming. The futures market suggests that the Federal Reserve is likely going to increase its target for the federal funds rate later this year or early in 2016. Most people take this to mean that interest rates are headed higher. It is not well understood that the Federal Reserve does not set or directly control intermediate and long-term interest rates that matter most to bond prices. The Fed uses open market operations to target a level for the rate that commercial banks charge between themselves on overnight loans – a rate referred to as the federal funds rate. This extremely short-term rate has a strong impact on the yield of money markets, bank savings accounts, and floating rate loans but less an impact on longer-term rates which are a function of market expectations.

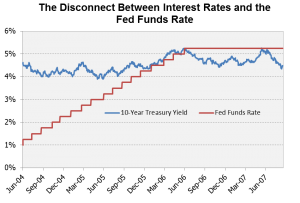

We need only go back to the last period of Federal Reserve rate hikes which began in June 2004 for a clear example of the disconnect between the Fed Funds Rate and longer-term interest rates. On June 29th, 2004, the day before the Federal Reserve began to increase rates, the 10-year US Treasury yielded 4.70%. Within three months of the first rate hike, the 10-year Treasury yield declined below 4.0%. That is, the Fed increased rates but bond yields went the opposite direction. A year after the first rate increase, the 10-Year Treasury yield remained below 4% despite the Fed Funds rate increasing by 2.0% over the 1-year time period. Purchasing a 10-year Treasury the day before the Fed started raising rates and holding it for a year resulted in a return of 10.1%. A 20-year Treasury held over that same time period earned 19.2%. (So much for the concept that you don’t want to own bonds when the Fed is increasing rates.)

If the market anticipates that Fed rate hikes are likely to trigger an economic slowdown, recession, or simply curtail any inflation pressures, expect longer-term bond yields to decrease, not increase.

Fallacy 2: Higher interest rates will hurt bond returns. This belief holds true in the short-term but not in the longer-term. If you buy a 10-year Treasury today and you’re seeking the highest nominal return over the next decade, the best case scenario is that interest rates rise dramatically immediately after you purchase the bond. This logic flies in the face of traditional short-term thinking because most people have been trained to associate rising interest rates with lower bond prices. It is true that the bond price will decline in the short-run and you would have been better waiting to buy the bond after rates increased, not before. But if rates immediately rise, you will be able to reinvest the coupon payments at higher reinvestment rates over the next 10 years which will make for a higher holding period return over the 10-year period than if rates had remained constant or declined. As demonstrated in the figures below, you actually earn an additional $5,460 from a $100,000 over the 10-year period when rates immediately increase by 2% rather than immediately decreased by 2%.

| 10-Year Scenario if: | Holding Period Return | Ending Value |

| Interest Rates Immediately Decline to 0.5% | 2.31% | $ 125,602 |

| Interest Rates Remain at 2.5% for 10-Years | 2.51% | $ 128,182 |

| Interest Rates Immediately Increase to 4.5% | 2.74% | $ 131,062 |

Fallacy 3: You should sell bonds in advance of Fed rate hikes. The first challenge to this flawed logic is simply the explanation addressed above that bond yields are not directly tied to the federal funds rate. The second challenge is that anyone who sells bonds has to determine an alternative for what to do with the sale proceeds. Cash pays nearly nothing and stock prices have historically provided lackluster results in rate tightening cycles. The third challenge is that timing the movement of interest rates has dumbfounded investors for decades and is likely to continue doing so. If you have the ability to know the future path of interest rates, you are better served to open a hedge fund and make outlandish profits than simply make a few dollars on your own portfolio. The final challenge is that bonds in a diversified portfolio serve an important role of providing protection in stock market sell-offs. While the S&P 500 lost 36.6% in 2008, an investment in 10-Year Treasuries gained 20.1%. If you’re worried more about sharp portfolio losses than near-term fluctuations, it is better to maintain a bond allocation than to abandon this protection.

What the Fallacies of Rising Interest Rates Mean to You

Humans are inherently biased to do something, a point that is not lost on Wall Street. We prefer action over inaction, regardless of whether inaction is optimal. Since Wall Street profits from investor activity, there will continue to be warnings of rising interest rates and what you can do to protect yourself as banks and brokerages seek to compel trading activity.

The point here is to introduce some key challenges with relying on public perceptions when it comes to the endeavor of interest rate speculation. For that matter, it should also be a reminder to remember the difference between speculation and investment. In the words of author Fred Schwed, Jr., “Speculating is an effort, probably unsuccessful, to turn a little money into a lot. Investment is an effort which should be successful, to prevent a lot of money from becoming a little.”

Leave A Comment