In 1996, Thomas Stanley and William Danko co-wrote The Millionaire Next Door – an examination of millionaires in America and the common qualities that continuously appear among this demographic. They spent nearly 20 years interviewing Americans with a net worth of at least $1 million and compared the behavior of what they termed “UAWs” (Under Accumulators of Wealth) with “PAWs” (Prodigious Accumulators of Wealth). Among their now well known conclusions were that PAWs did not have extravagant lifestyles that the outside observer might expect, that they spent less than they earned, and that they avoided leading a “status lifestyle.”

One chapter in this book is titled “You Aren’t What You Drive” and examines the vehicle purchasing tendencies of millionaires. There are several takeaways – that millionaires rarely ever lease vehicles, that they buy cars for function rather than for status, and that they usually take several months (not several days) to make a “price-focused purchase.” Yet despite the price-sensitive tendencies of millionaires, the idea that they tend to purchase used vehicles is simply not true. This myth became so pervasive that author Thomas Stanley eventually addressed the misunderstanding:

Over time the facts and words found in The Millionaire Next Door sometimes get twisted. It is a myth that most millionaire next door types only buy used cars. In fact, for every one millionaire that is used vehicle prone there are two who tend to buy new vehicles.

Stanley further addressed the used-car myth in his follow-up book, Stop Acting Rich. He explains that it was not that millionaires purchased used vehicles – it was that instead of buying luxury cars to express status, they purchased reliable cars and then kept these cars for nearly a decade or longer. According to research that Stanley summarizes, the most popular car brands purchased by millionaires during the period studied were Toyota, Ford, Chevrolet, and Honda. He also relays a surprising fact regarding luxury cars (BMW, Mercedes, Lexus, Jaguar, etc.): 86% of the people you see driving luxury cars are, in fact, not millionaires. This 86% crowd – and I’m paraphrasing Thomas Stanley here – were status conscious overspenders who failed to accumulate real wealth or achieve financial independence at a reasonable age.

Determining the Appropriate Amount to Spend on a Vehicle

Notably, there are no hard and fast rules about how much someone should spend on a vehicle. A common rule of thumb among personal finance gurus is that purchasers should always put at least 20% down, finance for no longer than 4 years, and spend no more than 10% of after-tax income on the combination of principal, interest, and insurance costs.

But these are effectively upper parameters that back into how much car someone can reasonably afford – not necessarily benchmarks that help assess how much a financially prudent buyer should spend on a vehicle. That question is tough, if not impossible, to reasonably answer. What we can do, however, is to quantify the financial impact of choosing one vehicle over a less expensive alternative or the lifetime benefit of driving each car a few additional years. Armed with such information, buyers who aspire to financial independence will hopefully be better equipped to make car purchasing decisions.

How Much The Luxury Car Really Costs

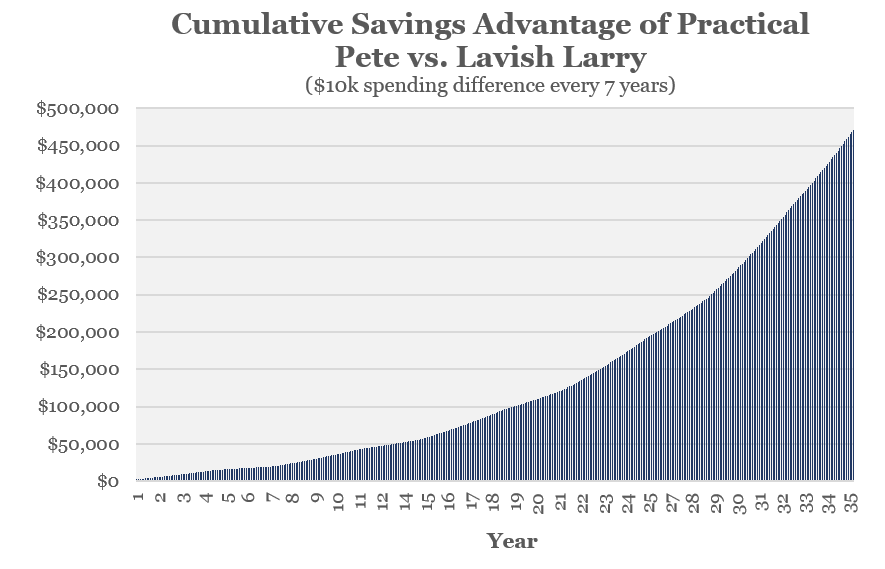

Let’s start with a simple scenario of two individuals, each buying a new car every seven years with 20% down on each purchase and the remainder financed over four years. Assume there are two identical buyers – practical Pete and lavish Larry. The only difference is that Pete spends $10,000 less on each purchase than Larry. It could be that Pete buys each car for $30,000 while Larry spends $40,000 or that Pete spends just $15,000 while Larry spends $25,000 – the math works the same if the differential is $10,000 (in today’s dollars, and then adjusted for inflation on future purchases).

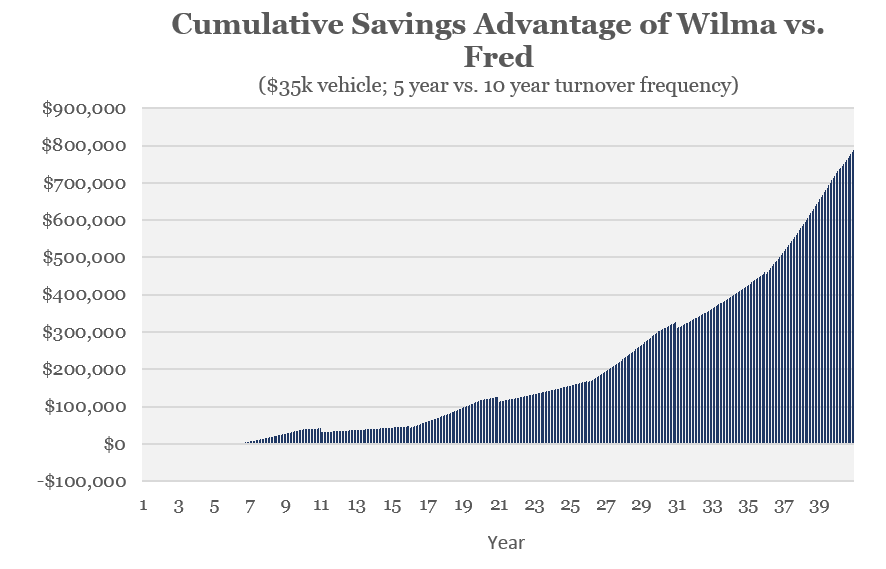

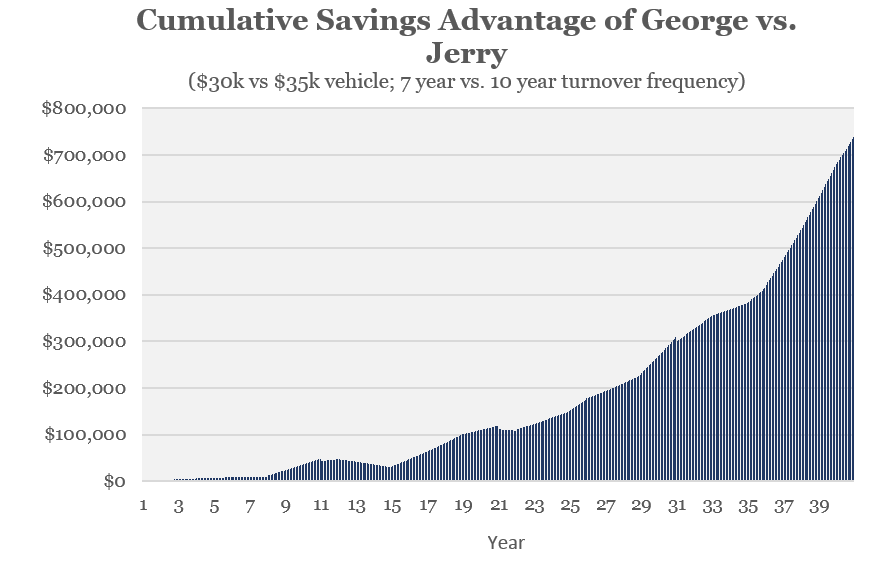

After 35 years, Larry has $471,185 less than Pete, all else equal We can take this example one step further and assume that both of Pete and Larry are married and that their respective spouses employ the same car purchasing discipline. Under these updated circumstances, lavish Larry and his spouse have $942,370 less in retirement savings than practical Pete and his spouse. To make the example even more real-life, we can compare the impact of purchasing America’s most popular family sedan, the Toyota Camry, versus purchasing America’s most popular luxury vehicle, the Lexus RX. According to TrueCar, the Toyota Camry has an average purchase price of $29,200 (note, this is average purchase price, not the higher MSRP). Alternatively, the Lexus RX has an average purchase price of $53,800. Assume that practical Pete and his spouse purchase two new Camrys every eight years – one for each of them. They drive their Camrys for these eight years and then trade them in for new Camrys. Meanwhile, Larry and his spouse purchase two new Lexus RX every eight years and similarly trade them in every time for a new RX. After 40 years of this cycle, practical Pete and his spouse have amassed a whopping $3,387,029 more in savings than Larry. Up to this point, we have examined the long-term impact of upgrading to a more costly vehicle while holding all other variables constant. Another controllable factor that can have a large financial impact is the length of vehicle ownership. Specifically, what happens if two new buyers, Wilma and Fred, each buys the same vehicle but Fred gets a new car every 5 years while Wilma drives her car for 10 years before trading it in for a new car? Assuming that they’re purchasing a $35,000 vehicle (today’s dollars) each time and keeping all the other assumptions from prior examples, Wilma winds up with an additional $787,075 after 40 years from having only purchased 4 vehicles during that stretch rather than the eight that Fred bought. At age 65, this gives her an additional $53,335 per year in retirement to spend. Of course, we have some clients who would say, “After 10 years of ownership, I’m just getting started with my car.” So assume Wilma drives her $35,000 vehicle for 15 years before buying a fresh new set of wheels. Under this scenario, she ends up with $1,140,639 more in savings than Fred after the 40 years. Lastly, it might be useful for some to understand the long-term financial impact of seemingly small differences in buying tendencies. Assume that there are two buyers, George and Jerry. George spends $30,000 on his new car while Jerry splurges each time and buys an upgraded version of George’s car for $35,000. George drives his car for ten years before replacing it with the current version of the same new car. Alternatively, Jerry replaces his car every seven years. If they begin this process and repeat it for 40 years, George winds up with an additional $738,035 in savings which amounts to added retirement spending power of over $50,000 per year in retirement. That is to say that not spending an additional $5,000 on each car purchase for bells and whistles and keeping each car for three years longer affords George an extra $738,035 after 40 years – to allow him financial independence at an earlier age, more travel and other experiences in retirement, or just the added peace of mind. All of this is not intended to express a view on right or wrong. It is not to suggest that car buyers should keep their vehicles longer or avoid buying luxury vehicles. To this point, I recently spoke with a financial planner who said that if he could convince his clients to stop buying luxury goods and vehicles, he was providing them value. I wholeheartedly disagree with this sentiment. That is, in my view, someone pushing personal preferences on his clients. Instead, the purpose here is to arm buyers with information – the estimated financial impact of more frequent car turnover or purchasing more expensive vehicles. It changes the calculus from, “Can I afford to spend an additional X dollars on a new car?” to “What other lifetime goals might be impacted by spending an additional X dollars on a new car?” I find that some buyers, armed with this information, knowingly choose to spend on luxury vehicles even when they understand it may mean delaying retirement several years. Alternatively, some buyers prefer to trade in for a new car every 3-5 years because they want the latest features even though they understand that this activity will likely compromise their ability to travel in retirement. These are simply called informed choices. While some may disagree with the choices, I’d still maintain that they are only bad choices if they are uninformed choices. Have questions or comments? Disagree with anything above? Want to understand the financial impact of your specific scenario? Feel free to use the comments section below or send an email.

Quantifying the Value of Driving Vehicles Longer

Spending Less and Driving Longer

Closing Thoughts

- This scenario, and all that follow, assumes a 5% financing rate, reinvestment rate of 8%, car price inflation rate of 3%, annual maintenance and insurance cost of 3% of car value, state sales tax of 6%, depreciation of 25% in the first year followed by 16% thereafter, and that the depreciated residual value is used to cover some or all of the 20% downpayment on the new vehicle purchase.

- Uses November 2018 annuity quotes from immediateannuities.com.

Leave A Comment