Hats off if you’re maximizing your 401k deferrals and reaching the federal employee contribution limit each calendar year: $19,000 in 2019 if you’re age 49 or younger or $25,000 in 2019 if you’re age 50 or over. Note: these limits have increased to $19,500 and $26,000 respectively for the tax year 2021. Additional congratulations if you’re maximizing these deferrals early in the year to really exploit the tax deferral and then shifting your savings to a different account later in the year.

Sadly, financial diligence and front-loaded saving can have a costly drawback if you work for an employer that matches contributions. You read that correctly. Aggressively maximizing your 401k contributions and working for an employer that matches those contributions actually backfires. Often. And in a big, costly way.

Consider the scenario where Dana makes $240,000 per year and gets paid bi-monthly. Her employer matches 100% of the first 6% of income that she defers to the company’s 401k plan. Dana is an aggressive saver and elects to defer 25% of her compensation to the 401k plan – resulting in contributions of $2,500 each pay period. Her employer kicks in a $600 match each pay period ($10,000 gross pay * 6%). Dana reaches her 2019 contribution limit of $19,000 on her eighth paycheck at the end of April.

Because she hits the contribution limit on April 30 and makes no contributions to the plan after this date, Dana also gets no employer matching contributions after this date. As a result, Dana’s total employer match for 2019 is $4,800 ($600 match per pay period * 8 pay periods).

Dana’s colleague, Will, has the same income of $240,000 but alternatively elects to defer 8.0% of his compensation to the 401k plan each pay period. By setting his deferral percentage to 8%, Will does not hit the statutory $19,000 contribution cap until the final pay period of 2019. In turn, he receives the 6% match for all 24 pay periods – collecting a total of $14,400 from his employer ($10,000 income each pay period* 6% * 24 pay periods).

Although Dana and Will each work for the same employer, each have the same income, and each contribute the same $19,000 to their respective 401k plans, they have dramatically different employer matches. Will receives three times more than Dana in 401k matching contributions over the course of the year: $14,400 versus $4,800.

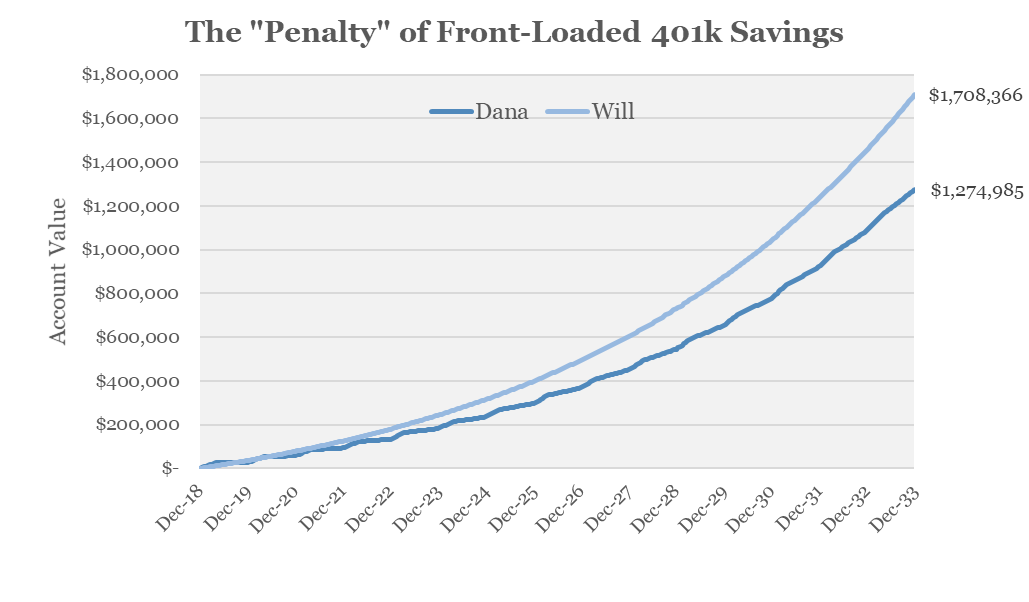

Now consider what happens if Will and Dana continue making the same contributions each year for the next 15 years and earn a 7% annual investment return. Because she’s contributing money earlier in the year than Will, Dana benefits more from investment growth on her employee contributions. Specifically, she earns an additional $45,950 in market gains over the 15 years by getting her $19,000 invested earlier each year.

Yet despite not saving as aggressively as Dana, Will has the last laugh. The additional matching contributions he receives plus the market gains on those contributions amount to an additional $479,331 for Will over the 15 years. That’s correct – an extra $479k. Even though he misses out on $45,950 of investment gains from saving earlier in the year, Will winds up with an additional $433,381 in his 401k ($479,331 minus $45,950). That is how much financial diligence costs Dana over a 15-year period.

Does Your Employer Penalize Aggressive Saving?

There are a few different ways that employers make matching 401k contributions and, as demonstrated above, the implications can be enormous for anyone who maximizes 401k contributions.

Payroll Matching – The most common matching formula is payroll matching where the employer contributes the match with each paycheck. If you contribute to the 401k plan during the payroll period and your employer uses payroll matching, you get the matching contribution for that pay period. If you don’t make a contribution during the payroll period, then there is no match. Will and Dana’s employer made matching contributions using this method.

Lump Sum Matching – Some employers simply match once a year as a lump sum, usually after the calendar year has ended. In this situation, it does not matter when you contribute to the 401k. As long as you contributed to the plan during the year, you get your full match regardless of how many pay periods in which you contributed.

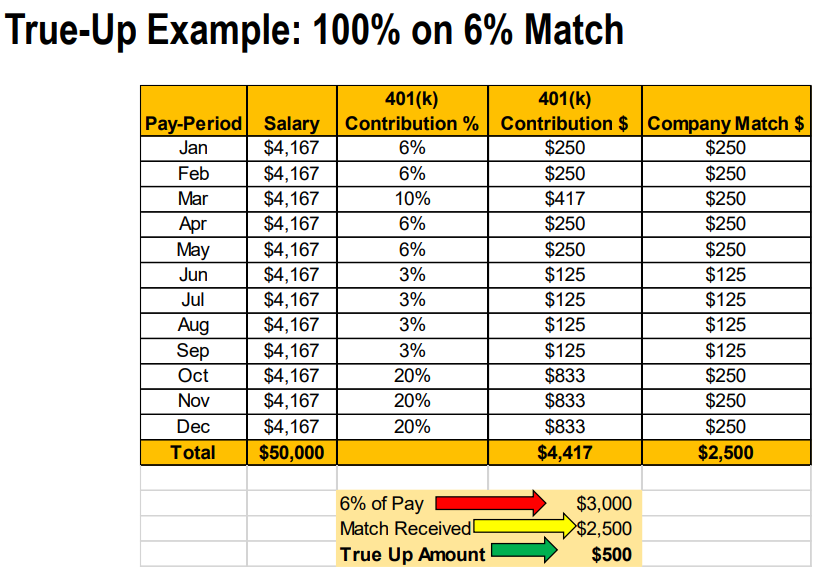

Payroll Matching with a “True-Up” Feature – This looks the same as payroll matching except that the employer provides a true-up feature to avoid “penalizing” diligent savers like Dana who front-load contributions. An employer best-practice, the true-up matching looks at your average percentage contribution to determine if you would have received a larger match by spreading contributions over the full year. If appropriate, the employer provides a true-up match to avoid the inherent penalty of simple payroll matching. Notably, this true-up feature has several varieties. Some employers true-up every pay period which would have meant that Dana would continue receiving matching contributions after April 30. Some employers true up once at the end of the year for all participants. Finally, some employers true-up once at the end of each year, but only for participants who are still employed at that time.

As long as your employer uses lump sum matching or a true-up feature, there is no downside to front-loading 401k contributions early in the year. Since most employers use the payroll matching formula with no true-up, employees in these companies who wish to maximize their annual contributions have to be careful about their contribution timing.

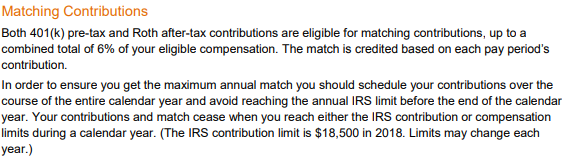

The best way to determine your employer’s matching method is to check with the plan provider/benefits department or to review the plan documents. Look specifically for the section that describes matching contributions. For example, the following passage comes from the plan documents for a large Atlanta-based employer that uses payroll matching with no true-up:

Alternatively, another large employer that uses payroll matching with a true-up provides an explanation in their benefit materials of the true-up:

What To Do If Your Employer Uses Payroll Matching With No True-Up

If you discover that your employer does not provide true-up matches and your desire is to maximize savings up to the annual 401k contribution limit, it’s time to do a little math.

Consider the example of 52-year old Barry who has an annual income of $400,000 and is eligible to contribute $25,000 to his 401k in 2019. His employer matches each dollar of 401k deferrals up to 4% of salary without a true-up. Barry simply needs to divide the $25,000 contribution limit by his income of $400,000 which results in an answer of 6.25%. He then wants to set his 401k deferral percentage to 6.25% before the first payroll of the year so that he spreads his 401k contributions over all pay periods and still hits his contribution limit of $25,000 by December 31.

There are a few possible wrinkles here. One challenge is that many employers require the deferral percentage to be a whole number (no decimals). In this case, Barry could round down his deferral percentage to 6% starting in January and then ramp it up in December to ensure he makes the full $25,000 employee contribution over the year. If he gets paid twice per month, setting the deferral percentage to 6% for the first 23 pay periods ($1,000 deferral per pay period) results in $23,000 saved and then increasing to 12% for the final pay period of the year gets him to $25,000 for the year while maximizing the employer match. There are, of course, many alternatives. For example, Barry could reverse the above example by setting his deferral percentage to 12% for the first pay period in January and then reverting to 6% for the remainder of the year. This gets him to the same place, albeit with more front-loaded savings.

Another common wrinkle is that employees may not have a good handle on their expected income at the start of the year. Variable, commission-based compensation or large mid-year bonuses often create such uncertainty. If Barry gets paid by commission, he should do the same math as above but use a conservative estimate of his full-year income when calculating a deferral percentage at the start of the year. Sometime in the 4th quarter, he can then increase or decrease the deferral percentage depending on how close or far his actual income will be from the anticipated income. In the case of large bonuses paid during the year, the same approach can be applied where Barry would just want to estimate his bonus and then modify his deferral percentage later in the year, as appropriate, to capture the full match and get the full $25,000 employee contribution.

Final Thoughts

While saving aggressively to a 401k plan is admirable and financially necessary for most people who aspire to reach financial independence at a reasonable age, the strategy for such aggressive saving may need to be modified to fit with an employer’s 401k matching approach. Anyone who works for an employer with a 401k match would be well-served to understand the employer’s matching formula and adjust appropriately to optimize.

Questions on whether you should be maximizing your plan or building liquidity on your balance sheet? Deciding between Pre-tax / ROTH / After-Tax contributions? Click here to schedule an Introductory Call, we would love to get to know you.