We made the case in this earlier post that Section 529 College Savings Plans present a huge tax saving opportunity for high income parents but that most fail to exploit the opportunity. Based on experience and observation, we cited five reasons that parents and grandparents fail to maximize the potential benefits. Two of those reasons were:

- Parents worry too much about overfunding 529 Plans; and

- Parents don’t fully appreciate the tax benefits of 529 Plans.

It is likely that if high income earners really understood the full tax benefits of 529 Plans, they would, arguably, not be worried about overfunding 529 Plans – they would be throwing every extra dollar of savings beyond tax-deferred retirement account (401k, 403b, IRA) limits into 529 Plans. There’s a strong case to be made that high-income earners could and should be sheltering hundreds of thousands of dollars from taxes in 529 accounts.

More and more, financially astute savers are starting to think of health savings accounts (HSAs) as lucrative retirement savings vehicles rather than as an account to pay for annual medical expenses. However, you’d be hard pressed to find anyone promoting 529 Plans as retirement savings vehicles. That was clearly never the intent of the government – they are defined as college savings plans, not “college AND retirement savings plans.” Yet, just as savers are using HSAs as a dual-purpose savings vehicle (current medical expenses and/or retirement expenses), astute savers should be thinking of 529 Plans in the same dual-purposed way – for education costs and retirement expenses.

What about 529 Plan contribution limits?

It is hard to know exactly why 529 Plan contribution limits exist but Congress probably wanted to discourage parents from overfunding college savings at the expense of retirement. Additionally, they may have hoped to discourage wealthy savers from using 529 Plans as an uncapped tax-efficient retirement savings vehicles.

Yet while Congress sought to limit excessive 529 contributions in the original law, they never put any enforceable restrictions in place. Federal law left and still leaves the maximum 529 Plan contribution up to each state. Each state is expected to use, as an upper limit, the estimated full cost (including room, board, books, etc.) of attending an expensive school and graduate school in that state. These estimates vary by state with per-beneficiary caps ranging from $235,000 to $520,000.

However, it is valuable to keep in mind a few important subtleties of these state-imposed limits:

- There are no penalties or extra taxes if a 529 Plan balance exceeds the state imposed limit because of investment growth. Funds can remain in a 529 Plan once the balance exceeds the state-imposed limit but no additional contributions are permitted unless the balance declines below the threshold.

- As a reminder, you can use the 529 Plan from any state and you can have multiple 529 Plans for the same beneficiary. Consider, for example, that you live in Georgia where the limit for the in-state Georgia 529 Plan is $235,000. Now assume that you’d like to get aggressive on front-loaded education funding and save $350,000 for the anticipated college and graduate school expenses of your new-born daughter. You could open a Georgia 529 Plan for the first $235,000 and then use another state plan for the next $115,000 or just open a single plan in a state like Utah or New York with higher limits.

- Parents and grandparents are often confused by language in publications and on the websites of various 529 Plans that suggests there is an annual limit on gifting to 529 Plans. This annual “limit,” which in 2018 amounts to $15,000, is not a ceiling – it’s a threshold at which contributions that exceed the figure must be reported on the IRS Form 709. Importantly, contributions beyond this level are not taxed or penalized. Without getting deep into the gift tax rules or the special 5-year rule for 529 Plans, the potential drawback of making a one-year contribution in excess of $15,000 is that, if not properly planned, it may hinder two parents’ ability to freely give more than $22 million to their heirs. So unless you’re worried about leaving more than $22 million to your children and grandchildren, you should really not be concerned with annual contribution “limits.”

Super-funding 529 Plans

What some member of The Joint Committee on Taxation likely recognized 20 years ago in the drafting of Section 529 legislation was that if they did not limit the contributions, smart taxpayers might start using 529 Plans as super-funded retirement accounts. He or she probably went through the math exercise and realized that even with a 10% penalty and taxes due on any gains for non-qualified expenses, the benefit of tax deferred compounding for a long-period of time could overwhelm the eventual taxes and penalty. Alas, Congress never imposed hard and fast contribution limits and so, 20 years later, the opportunity still exists.

Notably, the argument we are about to make is not that these accounts should be used purely as a retirement savings account. The argument, instead, is that the economic benefit of tax free growth is so robust for high-income individuals that one would be better suited to aggressively err on the side of overfunding versus underfunding.

Fred and Wilma save for college

Consider two parents, Fred and Wilma, who, back in June 1989, want to get an early start on college expenses for their newborn son, Pebbles. Fred and Wilma are high income earners so they face high tax rates and have heard about the tax benefits of using a 529 College Savings Plan. They decide to use the country’s most popular 529 College Savings Plan – Virginia’s CollegeAmerica 529 Plan. They contribute $50,000 to the 529 Plan and choose to invest moderately-aggressive since their daughter has nearly two decades until college expenses start – 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds. To keep things simple, they choose two of the 529 Plan’s largest funds – The Growth Fund of America (AGTHX) for stocks and The Bond Fund of America (ABNDX) for bonds.

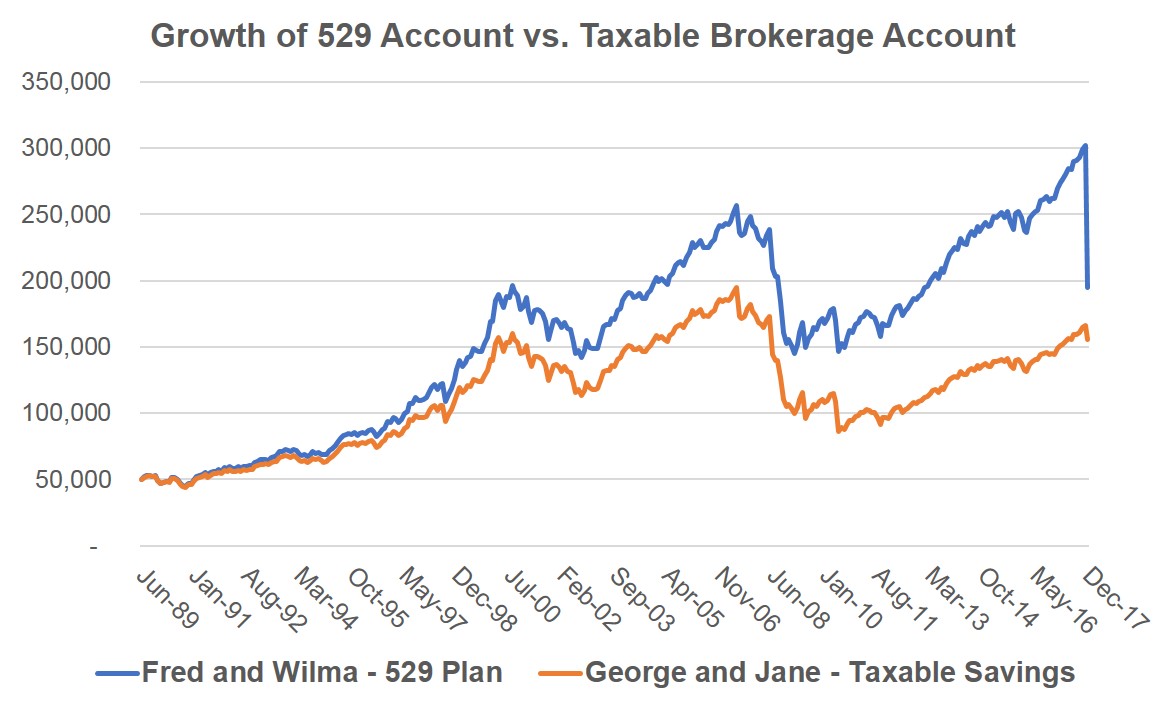

The only thing Fred and Wilma do for the next 18 years is rebalance once a year back to the 60% stocks and 40% bonds. They let the assets grow and after 18 years, they are ready to start withdrawing $20,000 each year to pay for Pebbles’ qualified education expenses. By this point, the original $50,000 has grown to over $256,000. They choose to withdraw $20,000 proportionately from the two funds for each year of college and continue to withdraw $20,000 every year for four years until Pebbles has completed college.

Despite a horrific stock market sell-off while Pebbles is in college, Fred and Wilma wind up with $146,626 after the $80,000 of combined education expenses are distributed. Unsure of what to do with the remaining funds in the two 529 Plans, Fred and Wilma do nothing. There’s a thought that Pebbles may attend graduate school but he never does.

Seven years after Pebbles graduates from college, in December 2017, Fred and Wilma retire. By this point, the remaining 529 Plan balance has appreciated to over $300,000. Knowing by now that Pebbles has no more schooling left, Fred and Wilma elect to liquidate the excess 529 funds and splurge on a lake cabin. They’re forced to pay taxes and a 10% penalty on the earnings portion because it is a non-qualified distribution. Still, after paying the taxes and penalty, they have $194,514 remaining to spend on their cabin.¹

George and Jane save for college

Now consider an alternate universe with parents George and Jane and their son, Elroy. Both scenarios are identical with one important exception. George and Jane are concerned about the restrictions of a 529 Plan and the penalties for withdrawing money for non-qualified expenses. As a result, they elect to open a regular brokerage account instead of a 529 and fund it with the same $50,000 in 1989. Everything else is identical – they buy the same two funds, in the same amounts, at the same time, and they rebalance annually in the same way. Then they wait 18 years, withdraw $20k per year for four years of college, pay taxes, and keep the remaining funds invested until their identical retirement date – December 31, 2017.

When George and Jane retire on the same day as Fred and Wilma, they go to their brokerage account to withdraw all the remaining funds that they didn’t spend on Elroy’s college. Their balance after paying capital gain taxes? $155,454. Not bad for a lake cabin but 20% less than what Fred and Wilma had remaining.

Fred and Wilma overfunded their 529 Plan, had to pay taxes and penalties, and still came out way ahead. Why? The tax advantage of the 529 Plan was so beneficial compared to the alternative that it overwhelmed the taxes and fees that had to come out at the end.

George and Jane had identical returns but each time a dividend, interest, or a capital gain distribution was paid by the fund, they had to pay taxes. They also often had to pay taxes when they rebalanced each June. These tax dollars added up with their high tax rates, leaving less invested for the future. Moreover, when they withdrew money to pay for Elroy’s college expenses, they not only had to withdraw $20,000 for each year of college but also had to pull out additional funds for the capital gain taxes that they owed. As a result of this tax drag, George and Jane have dramatically less money invested when Elroy finishes college than do Fred and Wilma.

The chart below shows what the two scenarios look like, with the example starting in June 1989 and running through December 2017². Notably, the large drop in the blue line at the end of the time period represents the taxes and penalties owed for the non-qualified 529 Plan distribution.

Now, what if the original scenarios stay identical with one change – neither Elroy nor Pebbles ever goes to college. Consequently, there are no qualified distributions for the 529 account and at the end of 2017, every dollar of growth in the 529 account is subject to taxes and fees. The result is that the two parents end up with almost identical amounts – Fred and Wilma with $297,344 and George and Jane with $298,444.

Closing Comments

In a 2017 article, we made the case that 529 Plans have far more flexibility to get excess funds out without penalty than people realize. Since we wrote it, Congress added even more flexibility by allowing 529 Plan funds to be used for elementary or secondary school education costs (up to a $10,000 per year, per beneficiary limit). We also wrote this article last year to discredit the common reasons for not aggressively funding 529 Plans.

Today’s article is simply intended to demonstrate the powerful math of tax free growth and how overfunded 529 Plan accounts, even after the fees and taxes for non-qualified expenses, are still likely to come out on top. Our advice again is to not let a lack of understanding or misconceptions about 529 Plans keep you from exploiting the opportunity. If you are a parent in the fortunate position of being capped out on tax-favored retirement accounts and trying to figure out where to optimally save the next dollar, we would again argue that the tax advantages and flexibility of 529 Plans make them dramatically underutilized by high income earners.

¹A state+federal tax rate of 40% was applied to pre-retirement income and a 20% rate for capital gains and qualified dividends. A state+federal tax rate of 30% was applied to the retirement 529 distribution. Rebalancing happened each June 1st.

²Interestingly, the 529 Plan advantage for Fred and Wilma could have been even greater if they took one simple step when they initially funded the $50,000. Had they opened one account for the $30,000 stock investment and another account for the $20,000 bond investment, they would have ended with more dollars due to the tax advantage of using two accounts instead of one. As with most 529 Plans, CollegeAmerica charges no account fees so there is no extra cost to have two accounts rather than one.