Anyone who attended summer camp as a kid likely equates marshmallows with two things – a fundamental ingredient in making s’mores and the only ingredient needed for a game of chubby bunny. When a psychologist hears the word marshmallow, however, the first thought may not be of s’mores or chubby bunny. Instead, a psychologist likely associates the word with one of the most famous behavioral studies ever conducted – an experiment that simply uses marshmallows and kids, minus the s’mores and chubby bunny.

The Stanford marshmallow experiment (which is best appreciated by watching this humorous video with over 2.5 million views) was first conducted in the late 1960s to examine delayed gratification. Children were offered the choice between an immediate marshmallow or two marshmallows, if they were willing to wait 15 minutes and not eat the original marshmallow sitting in front of them. Most children in the study said they would wait for two marshmallows. Yet of more than 600 children who participated in the original experiment, roughly 2/3 fell victim to temptation. Only 1/3 of the children waited the full 15 minutes and were rewarded with a second marshmallow.

That, however, is not where the findings of this marshmallow study end. When experimenters went back to review the test subjects nearly 20 years after the original test, they discovered that the children with the discipline and self-control to delay gratification in this simple test were more successful in nearly every measurable facet of their lives. Controlling for factors like age and sex, the “patient subjects” had higher SAT scores, less likelihood of substance abuse, larger salaries, performed better academically, and were healthier than the subjects who could not wait 15 minutes for the 2nd marshmallow as children. The test has been performed repeated times since the original experiment with the same findings.

A World of Immediate Gratification

Delaying gratification is difficult. Overwhelming evidence demonstrates that humans are not wired to be disciplined, whether it is children with marshmallows, adults firmly sticking to a diet, or investors maintaining a long-term strategy. Approximately 45% of Americans will make New Year’s Resolutions this month and yet only 8% will be successful in achieving those resolutions.

In addition to cognitive tendencies that drive us away from long-term discipline, we also have the world around us. It is challenging to avoid instant gratification in a world of Amazon Prime same day delivery, Keurig instant-coffee machines, and always-handy 4G phones. Long gone are the days of brewing a pot of coffee or waiting 30 seconds for dial-up Internet. We are barely willing to wait more than two seconds for an online video to load. Corporate executives rarely get the flexibility to ignore quarterly earnings for the benefit of a 5-year plan and coaches tasked to rebuild a program typically can’t afford 2 losing seasons without the threat of being fired.

The same need for instant gratification applies in finance. Far more exciting and entertaining than stories of diversification or long-term investing are the explanation of why stocks fell yesterday, how this morning’s economic data is going to impact interest rates this quarter, and where oil prices are headed over the next year. This captures viewers for CNBC, eyeballs for Yahoo! Finance, readers for the Wall Street Journal, and active trading for the big banks and brokerages. All of these businesses and their counterparts are incentivized to induce activity. The ubiquitous explanations of what happened to stocks yesterday and forecasts for the coming weeks compels activity and complicates the somewhat simple and successful process of long-term investing. Promoting short-term thinking and immediate gratification is in nearly everyone’s best interest, except the investor.

The Evidence of Discipline

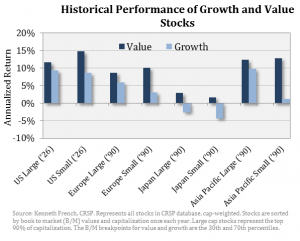

Many investors understand the benefits of long-term discipline but the evidence suggests that few practice it. It is admittedly not easy. Consider value investing – the basic concept of favoring cheap investments over expensive investments. Historical evidence demonstrates clearly that value investing results in higher returns when compared with growth investing – buying the more exciting, faster-growing investments. The evidence to support the “value premium” is considerable and it exists in nearly all markets and all long-term periods, as evidenced below.

Along with the empirical evidence, there are several rational explanations for the outperformance of value stocks. Included among those explanations is the easily relatable hypothesis that investors prefer good stories of fast growing investments and overestimate the persistence of high growth in the future, which causes them to overpay for growth relative to value investments.

Despite the overwhelming evidence and explanations of value outperformance, two irrational things persist. First, the aggregate investor ignores the fact that this anomaly exists and continues to make the same behavioral mistakes which resulted in the anomaly in the first place. Second, investors succumb to immediate gratification and give up on value stocks during their inevitable periods of underperformance. It is painful to stick with a proven strategy that disappoints in the short term.

Take the most extreme period of value stock underperformance and the most well-known (or perhaps most successful) value investor, Warren Buffett. By the start of 2000, the Internet was changing the economic landscape and boring old-school stocks were not only out-of-favor but basically left for dead. Value investing was allegedly a thing of the past and Buffett’s stock, Berkshire Hathaway, lost 44% of its value over a 20-month period during which growth stocks compiled a 47% gain. Doubts about Buffett’s age and ability to adapt to a new environment or just value investing, in general, were raised and investors gave up en masse. Of course, history confirms that this was merely one of the inevitable periods of underperformance that all investments, strategies, or asset classes will have relative to others. Long-term investors who maintained an evidence-based discipline were handsomely rewarded.

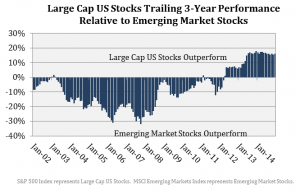

No investment is immune to short-term underperformance and yet investors are quick to make knee-jerk reactions in the quest for immediate gratification, often letting short-term noise or stories disrupt a long-term strategy. In the mid-2000’s, emerging market stocks were the asset class of the day and the widely popular story of “decoupling” was used as a justification to invest. The tide eventually shifted and today, the prevalent story is one of US economic growth leading the rest of the world. Both asset classes deserve to be part of a long-term strategic allocation but neither deserves to be the entire allocation, now or then.

What It All Means to You

What It All Means to You

The oft-quotable Warren Buffett said, “The stock market is a highly efficient mechanism for the transfer of wealth from the impatient to the patient”. Like Buffett, we rely on an evidence-based patient discipline that recognizes the randomness of short-term results. We admittedly understand that the irrational behavior flaws of humans leads us all to make investing mistakes and we seek to do three things as a result:

- Prevent ourselves from succumbing to emotional biases by sticking to a balanced investment discipline.

- Deter our clients from succumbing to emotional biases by developing a long-term plan.

- Exploit the emotional biases of others using evidence-based strategies like value investing.

For centuries to come, kids will likely eat marshmallows before 15 minutes elapses in the experiment and investors will pay way too much attention to last week’s payrolls report or Federal Reserve minutes that do not matter in the long run. But just as the children with a strong self-discipline end up more successful over the long run (not to mention getting two marshmallows), so should the disciplined investor.

Leave A Comment