January 2010: A period that financial journalists dream about. We were ushering in the new year of 2010 and significant impending tax law changes provided a bevy of important topics that consumers needed help navigating. There was the elimination of federal estate and gift tax, the return of IRA required minimum distributions after a one-year hiatus, pending expiration of lower capital gain tax rates, the new American Opportunity Tax Credit, and all kinds of changes to Roth IRA rules.

Seeking to simplify the tax code language when addressing these Roth IRA changes, financial media replaced complex terms like two-year conversion income split election, Roth recharacterization, and non-deductible contribution conversions with seemingly simpler phrases such as income spreads, do-overs, and backdoor conversions. It all started to sound more like play calls from a school-yard football game than important changes to the tax code. All that was missing was the get-open play.

A Law Change That Favors the Wealthy

For many successful individuals and families, the options to tax-efficiently save are limited. Individuals working for an employer can defer up to $19,500 ($26,000 if over 50 years old) in 2021 to 401(k) or 403(b) plans, assuming that top-heavy requirements are satisfied by the employer. Employees are occasionally offered non-qualified deferred compensation plans which allow for additional tax deferred savings but these have their own set of drawbacks including a lack of creditor protection, flexibility, or liquidity. Small business owners have other avenues which may allow for higher contributions but may come with a higher price tag including mandatory contributions for employees.

With the new Roth IRA rules of 2010, one unique opportunity for additional tax-advantaged savings became available to a large number of tax payers. Prior to 2010, the option to convert assets from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA was limited to taxpayers with less than $100,000 of adjusted gross income. The Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act lifted that restriction on January 1, 2010. Anyone, regardless of income or filing status, could thereafter convert traditional IRA assets to a Roth IRA. Middle class families and even the wealthiest of Americans could, for the first time, take advantage of some unique opportunities.

The opportunity remains under utilized by the average taxpayer. When we describe the opportunity (called the “Backdoor Roth Conversion”), we generally have to first explain that it is not an esoteric and risky tax strategy that will likely result in an audit.

Before we explain the actual technique, it will help to briefly explain some rules regarding Roth and Traditional IRAs.

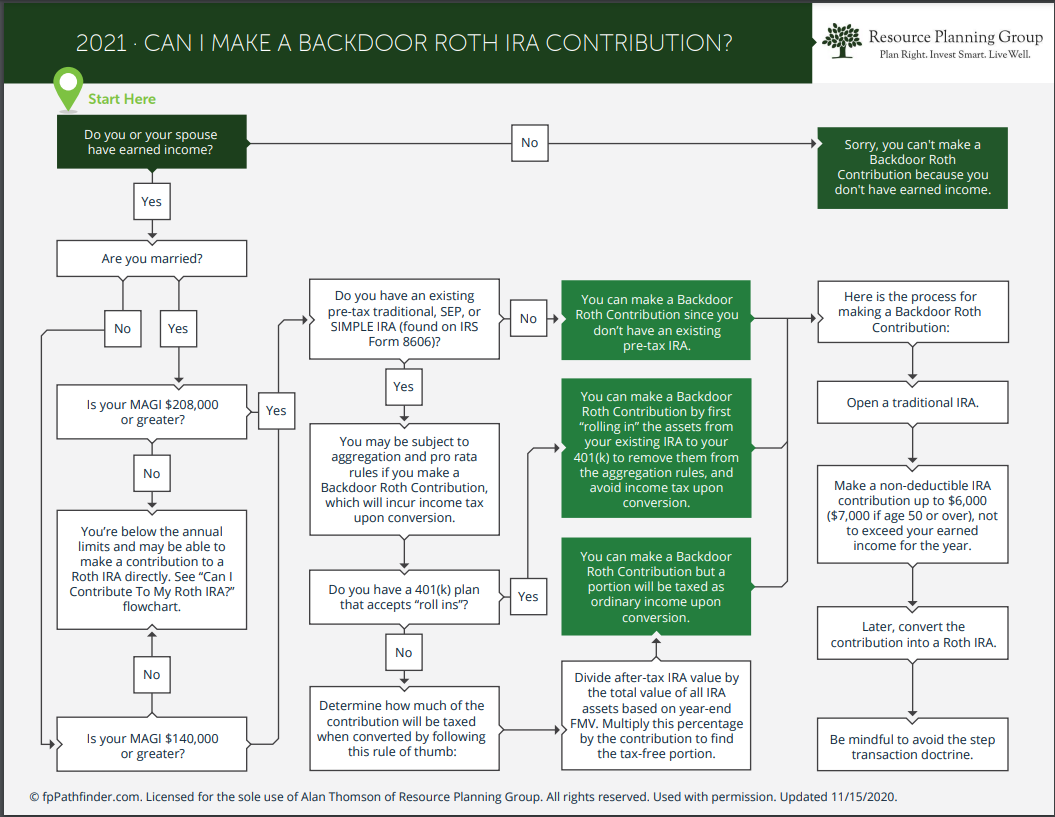

The Front Door is Locked. The Roth IRA allows taxpayers to contribute already taxed dollars to a retirement account that will benefit from tax-free growth in the future. However, IRS rules prevent any family with more than $208,000 (2021) of income or any individual with more than $140,000 (2021) of income from making contributions to a Roth IRA.

The Side Door is Locked. The Traditional IRA allows taxpayers to make contributions to a retirement plan and deduct the income for tax-purposes. Instead of being taxed in the year of the contribution, as with the Roth, the taxpayer is taxed on the income and associated gains at some point in the future when the assets are eventually distributed from the IRA. The rules for making deductible contributions to a Traditional IRA are slightly more complex than the Roth as they depend on access to a workplace retirement plan such as a 401(k). Without navigating through the details, the key point is that families or individuals with income in excess of the $208,000 and $140,000 figures above are also prevented from making deductible IRA contributions.

The Back Door is Open. The potential good news for higher income earners is that there are no income limits on the ability to make non-deductible Traditional IRA contributions. Anyone with any amount of compensation income, even individuals making 401(k) or 403(b) contributions, can contribute up to $6,000 to a traditional IRA ($7,000 if over 50). This also applies to individuals without compensation income but with a working spouse since the income is treated as joint income. As the name implies, the non-deductible Traditional IRA contribution is not tax-deductible but that issue is cleared up by the logistics of the backdoor Roth conversion.

The Backdoor Roth Conversion

With these rules in mind, coupled with the ability of anyone to convert from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, consider the following possibility.

You are married and your combined 2021 income exceeds $208,000 such that you are prevented from making Roth or deductible Traditional IRA contributions. You make a $6,000 non-deductible contribution to a Traditional IRA for yourself and another $6,000 contribution of the same kind for your spouse. Immediately following these contributions, you convert the $6,000 from each Traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs.

There are no tax consequences from this two-step process and you now have sheltered $12,000 in tax-free accounts so that all future income or gains on this money avoids any taxation. Although high income prevented you from contributing to a Roth directly, this backdoor Roth conversion achieved the same result without running afoul of any rules or restrictions. The diagram below depicts all of this visually with 2021 dollar amounts:

There is one challenge to this backdoor Roth strategy suggested by the asterisk in the diagram above. The process only works as described if you do not already have funds in a Traditional IRA, either from prior year contributions or via a rollover from a previous employer plan. If a Traditional IRA already exists, there are still work-arounds. The most-effective solution is to rollover any existing IRA assets into your current employer-sponsored retirement plan such as a 401(k) or 403(b) before executing the backdoor Roth conversion. This solution depends on your employer plan’s rules but most large plans and many small plans allow current employees to make rollover contributions. Once all existing IRA funds have been rolled into an employer plan, you can seamlessly initiate the backdoor Roth conversion.

Practical Implications

It is rare for new tax laws to strictly favor high income earners but that was the case in 2010 when the $100,000 income limit was lifted for Roth conversions. The removal of this restriction created a compelling avenue for income earners to save additional retirement funds via the backdoor Roth conversion.

If you have already maximized your workplace retirement plan and are not taking advantage of this opportunity, you are not alone. The process does necessitate an extra step or two and can get tricky if existing IRA funds exist so it may be useful to call on the assistance of a financial advisor. That said, the backdoor conversion is more than another backyard football play and adds another useful tool in helping to save tax-efficiently for retirement.

Leave A Comment