The thing I find most interesting about investing is how paradoxical it is: how often the things that seem most obvious—on which everyone agrees—turn out not to be true.”

–Howard Marks, Co-Founder Oaktree Capital Management

You may have heard the saying that “economists (and/or markets) have predicted 9 of the last 5 recessions.” Perhaps then, you would not be surprised to learn that economists have a poor track record of correctly forecasting our economic future. Economic predictions should therefore be taken with a healthy degree of skepticism. As the title (hopefully) suggests (and having misplaced our crystal ball), we are not predicting an imminent rise in interest rates. However, we know it is a top-of-mind subject for many investors and thus felt a blog post was warranted.

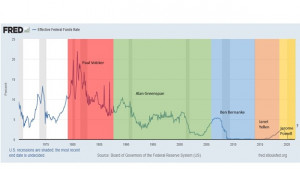

For the last 40 years, spanning the tenures of 5 Federal Reserve Chairs, interest rates on benchmark 10-Year U.S. Treasuries have followed the glidepath of a brick, falling steadily from the peak, double-digit 15%+ level witnessed in 1981, to the scant 1.4% rate available today. In fact, this rate has touched 3% just 3 times in the last 10 years. The long, secular decline in rates traces its inception to the Federal Reserve of Paul Volcker, whose aggressive tightening campaign in the late 70’s helped quash runaway inflation. However, Volcker’s actions also precipitated a severe recession in 1982, featuring double-digit unemployment. Volcker’s necessary (though unpopular) actions cleared the deck and set the stage for The Great Moderation, an ensuing economic expansion characterized by more stable growth and moderate inflation, lasting for the next 25 years.

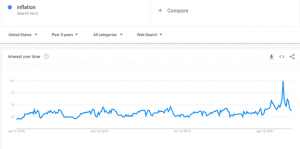

Today, there are fresh fears of rising inflation as the economy emerges from a self-imposed COVID-19 hibernation, interest rates remain at historically (if not artificially) low levels, and both fiscal and monetary policy has been aggressively stimulative. Against this backdrop, the strengthening demand of a recovering global economy is running up against still-disrupted supply chains, resulting in a surge in inflation measures. With expectations for a more “normalized” Fed policy in the future after a period of unprecedented stimulus, many investors are now wondering if now is the time to discuss the prospect of higher interest rates. With conventional wisdom telling us that rising interest rates equate to lower prices for bonds, some are wondering if they should proactively sell bonds to avoid anticipated losses. Perhaps surprisingly, the answer is not necessarily. At the very least, before taking action investors should consider some faulty logic and misconceptions around the topic of rising rates which may otherwise encourage them to hit the sell button.

Misconception 1: Higher interest rates are coming. A common misunderstanding about monetary policy is that the Federal Reserve directly sets interest rates, pegging them to formal targets that are determined by policymakers behind closed doors. This is not an accurate statement as the mechanics in which interest rates are set are far more complex. The Fed uses a limited number of very powerful tools at its disposal to influence the direction and level of rates towards targets it believes to be consistent with its dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment. Chief among these is setting the discount rate—the very short-term rate charged to eligible financial institutions to borrow from the Fed’s discount window. Historically very few banks use the discount window, but the discount rate helps set a baseline level on which other very short-term rates are set. However, when it comes to longer-term rates, it is market forces and the macroeconomic environment which ultimately determine their direction and levels. True, the Fed is a massive player in the markets (armed with a printing press) and can impact markets with relative ease over the short-term. Still, the Fed must work through the markets to achieve & sustain its policy objectives.

The chart below helps to illustrate this point. Note that the Effective Federal Funds rate (the one over which the Fed arguably has the most influence) is very closely tracked by the short-term 1-year Treasury yield. However, the 10-year rate is much more volatile, and moves largely independent of the shortest-term maturities. Interestingly, in the 2 most recent rate tightening cycles (2004-2006 and 2016-2019), yields on the 10-year were little changed. Thus, while a hawkish change in Fed policy could generate upward pressure on interest rates, it does not necessarily guarantee that higher rates across the entire yield-curve are a foregone conclusion.

Misconception 2: Higher interest rates are bad for the economy. It is true that higher interest rates act as a curb to economic growth as they increase the cost of borrowing, making it more expensive to finance large projects like buying a house or car, or growing launching and growing a business. However, there are positives that can come with higher rates as well. Savers who have been punished by low rates may see higher-returns on fixed-income investments, providing for a more secure retirement. Higher rates may put a damper on animal spirits and prevent excessive speculation in risky assets, easing fears over potential asset bubbles. Higher rates may even lead to riskier, poorly capitalized companies going out of business, cleansing and purging excess and waste from the system, leaving it stronger and more efficient. While higher rates could eventually lead to an economic contraction it is impossible to know at what level that could occur. That said, recessions are a natural part of every business cycle and ultimately cannot be avoided.

Misconception 3: Rising interest rates will hurt bond returns. At first this may seem obvious since there is an inverse relationship between bond prices and their respective coupons. Rising interest rates therefore imply that bond prices are falling if rates are rising, so selling bonds now can prevent future pain, right? Over the short-term this is true and traders and short-term speculators are more likely to be hurt when rates are rising. However, the same is not necessarily true for long-term investors. This is because a bondholder can opportunistically and systematically reinvest their periodic interest payments into higher-yielding securities as rates rise, gradually improving their returns. Further, if a bond investor holds onto their bonds until maturity, they should not lose money as declines in principal from falling prices will be more than offset by the income payments received until their bonds mature at par. To be sure, it is true that rising inflation is a risk to the purchasing power of fixed-income securities (Please see our recent posts on Series I Bonds for more).

Misconception 4: The smartest move is to sell bonds before the Fed raises rates. There are several flaws with this line of thinking. First, we’ve already showed that the Fed’s raising/lowering of its target interest rates is no guarantee of a change in market rates—especially on rates greater than a few months out. Secondly, if a bondholder sells his bonds, he faces a conundrum of what to do with sales proceeds, as he now holds cash earning 0% when he was previously earning a positive rate of return. Putting the proceeds into an asset class like equities entails greater risk and the potential for, but no guarantee of higher (or lower) returns. In fact the risk of outright loss on equities is a distinct possibility.

Another problem with the strategy of selling bonds before the Fed raises rates is that it implies the ability to successfully time the market. Empirical studies have consistently shown that it is virtually impossible to time the market in a manner that consistently improves long-term performance. People are often hurt by their own overconfidence (believing that they have some innate knowledge or edge that will allow them to achieve greater profit by getting ahead of the crowd). Usually, when something is widely known by the general public it has already been “discounted” by markets and any perceived “edge” has been all but eliminated. This is because the more widely known that information is, the less valuable it is. Often, once something has become “consensus information” a turn/reversal may not be far away. Is it possible that the inflation scare of 2021 follows a similar script? Lumber prices recently collapsed by the most on record in June. A spike in rental car rates caused by COVID-19 travel restrictions and compounded by a shortage of electronic chips used in car production looks like it could ease as chip manufacturing companies ramp up capital spending to relieve supply shortages. These recent developments could alleviate some of the inflation fears and some of the upward pressure in rates could ease if inflation fears subside. To wit, 10-year rates which had surged from 0.50% to 1.7% as the economy reopened, have recently pulled back to the 1.4% level.

Misconception 5: It is necessary to do something because things are changing. Humans are generally biased towards action over inaction. There is a natural, emotionally driven urge to take action in the face of discomfort and change. However, our emotional impulses often do us a disservice, encouraging us to take actions that alleviate short-term discomfort, often at the expense of long-term gain. It is important to remember that bonds serve a valuable role in a diversified portfolio. They are historically more stable than stocks and can provide ballast, providing asset diversification, lowering overall portfolio volatility, and helping to smooth long-term performance.

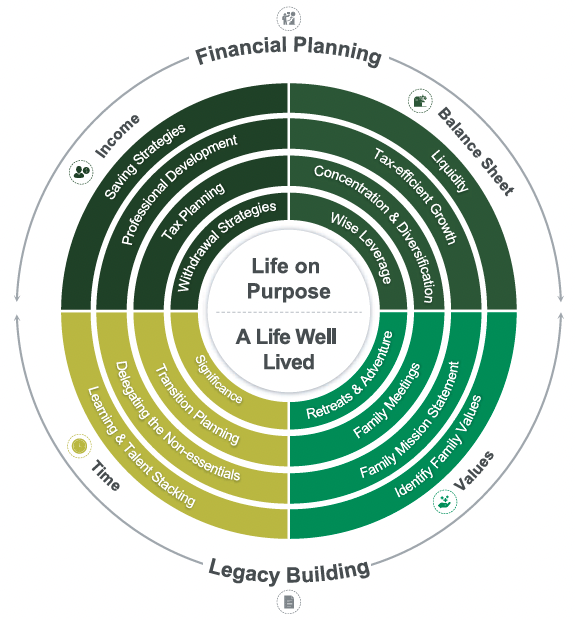

To improve the odds of long-term financial success, we prefer to focus our resources and efforts on the things we have the most control over. That includes controlling spending, efficiently managing cash-flow, optimizing taxes and making smarter financial decisions. We invest client assets in diversified portfolios across multiple asset classes, using low-cost ETFs and mutual funds. We don’t try to outsmart the markets, rather we use a regular and disciplined rebalancing process to maintain consistency with our target portfolio allocations while remaining vigilant, monitoring for risks and changes that could necessitate a more significant adjustment to our investment positioning.

Leave A Comment