The most interesting research project I worked on in graduate school was a study of statistical inefficiencies in sports gambling markets. My small team of fellow classmates hypothesized on all kinds of possible anomalies in sports. Was the over/under line inefficient when high scoring NBA or NFL teams were competing? Were teams coming off a bye-week more likely to win against the spread? Was it useful to bet against teams at the end of a long road trip?

Of all the hypothesized anomalies we examined, one stood out as the most statistically robust. We hypothesized that college football betting lines could be swayed by two common behavioral biases. First, the favorite bias which indicated that gamblers bet more often on the stronger team. Empirical evidence supported this bias in sports such as Major League Baseball (Woodland and Woodland, 1994), NBA basketball (Paul and Weinbach, 2005), and NHL hockey (Woodland and Woodland, 2001). Research demonstrated that excessive betting on favorites caused underdogs to win versus the spread more often than was expected.

The second bias we hypothesized would impact college football betting lines is called the availability heuristic. People overestimate the importance of information that is available to them – what they know. We reasoned that alumni and fans would be more likely to bet on their favorite team or alma mater. If true, larger schools with bigger fan bases would tend to be over-bet. When behemoth Ohio State played little Central Valley Community State, we estimated there would be an inefficiently disproportionate amount bet on Ohio State.

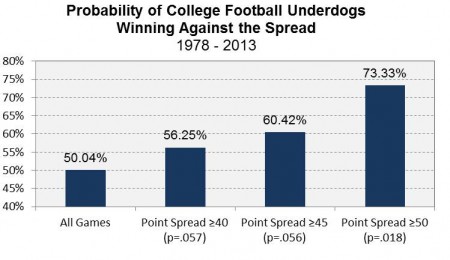

The hypothesis played out in the results. These two biases both inefficiently lined up bettors on the side of the big schools who were heavy favorites against their smaller foes. Updating the study through the 2013 season, there remains a meaningful statistical advantage when betting on the heavy underdog.

What Does College Football Betting Have to do with Investing

What Does College Football Betting Have to do with Investing

There are two important learnings from the examination of college football betting that can be usefully applied to investing.

Investors gravitate to what they know and what they like just as sports bettors disproportionately bet on their favorite teams. Research demonstrates that investors are more likely to buy stock of companies that provide products or services they know and like (Keloharju, Knupfer, Linnainmaa, 2012). They allocate too much to stocks within their home country (Hasan and Simaan, 1999). Most dangerously, individuals inefficiently concentrate in the stock of their employer (Meulbroek, 2005).

It may be psychologically comforting to buy what you know or bet on your favorite team but it is admittedly neither rational nor economically optimal. Although famed investor Peter Lynch told investors to “buy what you know”, this flawed wisdom leads to unnecessary risk and suboptimal portfolios.

Investors irrationally favor exciting stocks and good stories just as sports bettors disproportionately bet the heavy favorite. We naturally gravitate to fast growing investments or clean asset classes, seduced by the recent past. As a result, investors too often tend to ignore the fact that expectations for the future are built into the current price.

Consider the case of Russia which in 2014 was dealing with trade sanctions for its seizure of Crimea, recession, stagflation, and the ruble’s collapse. Within this economic malaise, the Russian stock market trailed every developed and emerging market in the world during 2014, losing 46.3%.

Entering 2015, Russia looked like a 56 point underdog. That is, the Russian stock market traded at 5.3x earnings, an enormous discount of nearly 70% relative to its history and its fellow countries. Russia didn’t need to win the game – it merely needed to lose by less than 56 points for the stock market to be a good investment.

This is precisely what played out in 2015. Vladimir Putin remained defiant of the west and sanctions continued. Energy prices plummeted, hindering the heart blood of the Russian economy (25% of GDP). The two largest rating agencies, Moody’s and S&P, both downgraded Russian debt to junk in the first quarter of the year. Yet the Russian stock market outperformed every developed and emerging market country in the first 9 months of 2015, except Hungary. This strong market return came not because Russian growth was positive (-2.2% and -4.6% in the first 2 quarters of 2015) or because oil prices rallied (-13% in 2015) but because the reality was not as bad as the expectation. Russia may have lost but they lost by fewer than 56 points.

This is not intended to make the case for Russia as a good or bad investment. It is a reminder that price matters. Successful companies generally have lofty expectations and struggling companies generally have low expectations. The key, as a wise friend says, is to find investments with short-term issues priced as though they are permanent problems. Whether those investments are currently emerging market stocks or the energy sector or some other component of the market will be determined with time. What we, as investors, can do is to rationally consider the expectations.

“If You’re Gonna Play the Game Boy, You Gotta Learn to Play it Right”

A strong case has been made by respected behavioral economist Richard Thaler that sports betting markets provide a better testing ground for market efficiency and human rationality than investment markets. Says Thaler, “each bet has a well-defined termination point at which its value becomes certain.” Alternatively, investment markets do not have an end date which means feedback is littered with noise and more difficult to test for rationality.

We can collectively do well as investors to learn from the demonstrated irrational biases of sports bettors. That means recognizing that glamour stocks or hot asset classes probably have lofty expectations and that betting on the heavy favorites is often a sucker’s bet. It means that investors will be well served to aggressively venture beyond their home country, their favorite company, or sectors they know best. It lastly means that the best investment is often the 56-point underdog, where short-term issues are priced as though they are permanent.

Leave A Comment